It’s high noon and the pizza is nowhere to be seen.

About halfway between West Vancouver’s library and the yacht club, right along that stretch of Marine Drive where the sidewalks become irregular, there’s a government building behind a fence. A teacher stands by the building’s entrance. He’s waiting for pizza. And, more importantly, he’s waiting for the reaction the pizza will trigger.

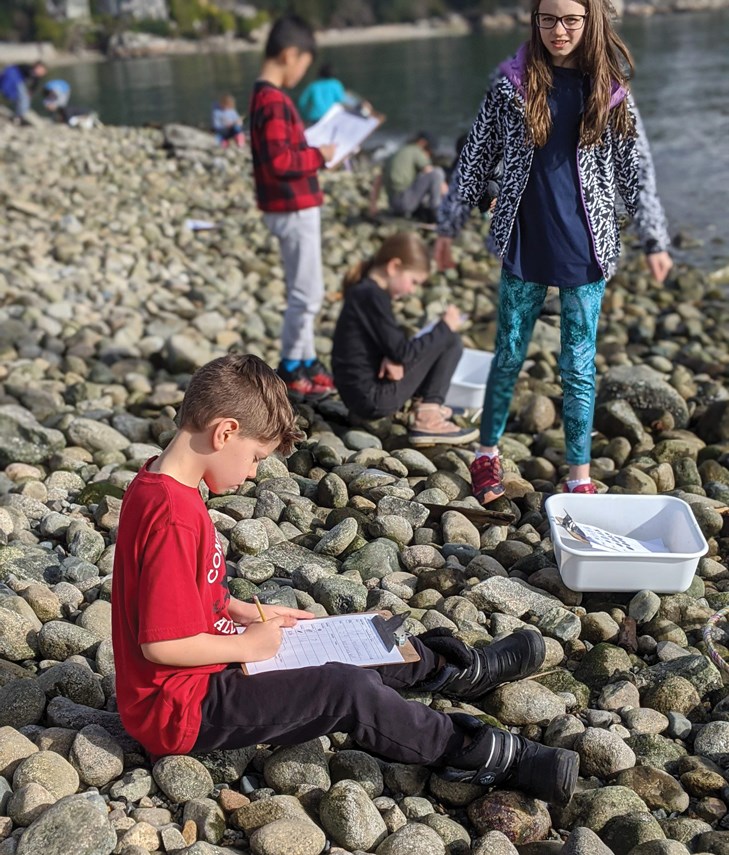

Eagle Harbour Grade 4/5 teacher Stephen Price rips packaging from a stack of juice boxes as a crowd of young scientists, his students, laugh and talk in front of their experiments.

As part of their plant biology research, the class made three visits to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ Pacific Science Enterprise Centre on the 4100 block of Marine Drive.

As a boy, Price remembers walking at Lighthouse Park and wondering: “What is that place?”

Prior to 2015, the lab was generally closed to the public.

“The place was at one time called a walled city,” recalls Steve MacDonald, the head of environmental and aquaculture research at the centre.

As the centre’s doors eased open over the past five years, Price did his best to shoehorn his students through that corridor.

“It’s really great for [students] to see people in West Vancouver who are doing world-leading science every day, seven minutes away from our school,” he says.

There’s an image of the scientist – wide eyes, white coat, white hair – an incomprehensible genius toiling in a lab.

But this extended field trip – featuring three visits over three months – is a way to show how “real science” happens, Price says.

The kids have toured the centre. They’ve seen posters produced by real scientists and they’ve also observed that those posters are very similar to the posters they make.

“At every stage we’ve got scientists reinforcing that learning,” Price says.

They’ve learned about science questions, designed experiments and controlled for variables. But more than that, they’ve developed an understanding that they’re not learning to be scientists. They’re scientists learning to be better scientists.

. . .

“A lot of science field trips are quite shallow,” Price says.

But this is less of a field trip and more of a “mini-academy,” notes PSEC outreach co-ordinator Sarah Board.

Price agrees as he takes another look at the long driveway leading to the centre.

“Just praying that the pizza will arrive,” he says. “I did call them.”

It’s not that he’s hungry – though there is that – it’s the hope that pizza will act as a solution to an educational experiment.

Once the pies arrives an email goes out to scientists throughout the centre.

“Who’s not going to come to pizza?” Price asks. “Everyone’s having a nice lunch but I’m also leveraging 45 minutes of scientist time, times 19. So I’ve got a one-to-one adult to student ratio here.”

Sure enough, as Price plunks boxes of pizza on a table the students cheer and scientists step out of elevators and flit down hallways to mingle with students and inspect experiments.

As dough and mozzarella fill the air, Macdonald notes one plant’s near death experience after being weaned on an energy drink.

“You didn’t kill ’em,” he observes, inspecting the sorry condition of the Gatorade-fed plant. “Maybe too much sugar?”

Sugar may not be the key ingredient, reasons Grade 5 student Kia Boedker.

Halfway through his experiment contrasting the effects of water vs. Powerade on plant growth, Boedker shifted gears.

The Powerade had yielded no growth at all. So, Boedker switched to a solution with the same amount of sugar as Powerade.

“I watered it and it actually grew,” Boedker notes. “So something other than the sugar in the Powerade kills it.”

On the other side of the room Grade 4 student Charlie Brandt, the creator of the Charlie and the Red Bean Stalk experiment, has discovered the scientific value of a mistake.

Brandt started with two plants side by side “by a nice sunny window.”

Each day after school Brandt would water one plant with water and the other – in an attempt to investigate altering its colour – with red food colouring.

“And then I mixed the plants up, I put red food dye in both of them,” Brandt says. “So, yeah.”

While the red is more pronounced in one plant, the roots of each carry a reddish tinge.

On the other side of the room, MacDonald examines a study of hybrid plants.

Sounding both analytical and not a bit discouraged, Mason Woodley initially summarizes his experiment in three words: “It’s a fail.”

Using dinosaur kale, bean plants and a WiFi router, he was going to test what would happen to a hybrid plant that was exposed to electromagnetic rays. It didn’t quite pan out, he says.

“We were going to open houses basically every day after school,” he offers. “So we never really had time to transplant the hybrid plant.”

It’s a fail, a scientist agrees. That doesn’t mean it’s a failure, he tells the student.

Discussing the experiment, Woodley is all smiles.

“I made these two pages showing why I failed,” he explains, noting a previous experiment that involved a homemade Bunsen burner made out of tinfoil and a kettle.

Discussing his future, Woodley says he’d like to do something in chemistry and physics. “And sometimes biology,” he adds, noting his curiosity about the difference between the DNA of strawberries and blueberries.

As lunch ends and the kids head outside to get a little sunshine, MacDonald discusses failure and whether or not it really exists in science.

“There’s no such thing as failure,” Macdonald says. “It’s just an opportunity to learn.”

But for Price, the word failure is vital.

“Part of my practise here is to de-fang failure,” he says. “Failure is part of the process.”

What’s important, Price continues, is that students learn to distinguish between good and bad failures.

As pizza plates get cleaned up, Macdonald ruminates on the centre’s former reputation as a gated scientific community.

“We’re struggling with what outreach really is,” he says.

It takes a “very flexible” educator to integrate their curriculum into the lab’s research.

Asked whether the scientists enjoy having the students in the lap, MacDonald considers.

“Depends,” he says, explaining he’s tried his darndest to make participation voluntary.

“The people who don’t want to do something like this probably shouldn’t be involved.”

Personally, he loves to hear young people use the word “hypothesis.”

Those plant experiments were part of a larger experiment about whether students could find something meaningful in the lab. Early indications are positive, Price says, noting many of his students were stressed out before the big reveal.

“When we make learning real this way it gives them a much stronger impetus to take it seriously,” Price explains. “And also it creates that meaning.”