The most difficult part was telling the one he loved that something didn’t seem right.

Allan Maynard had noticed that his wife and partner of more than 50 years was starting to slip up. She was forgetting things, she was having trouble remembering, and certain daily interactions just weren’t registering quite right. When Maynard brought it up, Margrit, his wife, objected.

“It’s such a gradual thing. You have periods where you adjust and get used to it,” he says, but then: “I think one of the hardest parts for me was having to tell her that we needed to get her to the doctor.”

Margrit’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis arrived in 2014. She’s since moved to a care residence and now communicates non-verbally. Her husband visits her all the time.

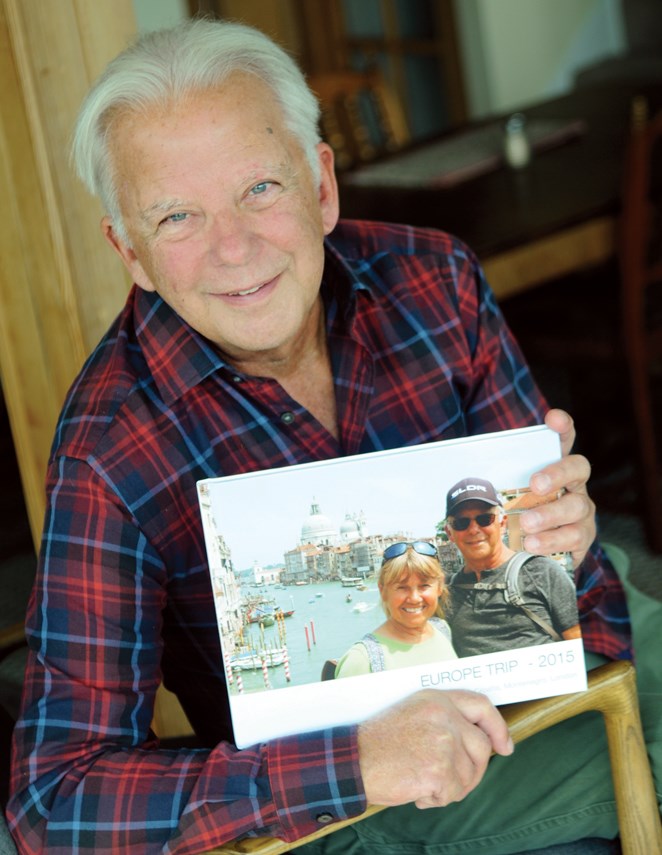

“If it’s not raining, I get her out for a walk,” he says. But for those days when the weather doesn’t hold up, the couple pores through photo books which Maynard compiled from the couple’s extensive travels over the years. Looking through the photographs allows the couple to commemorate their journeys and step into memory lane together, according to Maynard.

Maynard will be sharing his experiencing standing alongside and caring for someone living with Alzheimer’s disease during an Alzheimer Society of B.C. open house event in North Vancouver later this month.

The purpose of the event, held in conjunction with January’s annual Alzheimer Awareness Month, is to share more about the work the society does and help educate people on the harmful misconceptions which keep Alzheimer and dementia patients from living their best lives.

“In the early stages I was trying to play it down, just for my own sake, and I think some of our friends were getting a bit worried, wondering: ‘Does Allan realize what’s happening here?’” he says. “The more awareness, the more people can help. I think everyone’s willing to adjust their own behaviours and to accommodate.”

Many people living with Alzheimer’s or other dementias, simply put, may experience embarrassment or shame at their diagnoses, which further stigmatizes them and can even lead to them becoming socially isolated, according to Maynard.

“People can’t deal with this alone, they need all the support and help they can get. I’ve appreciated the support I’ve got from the Alzheimer Society.”

Barbara Lindsey, the Alzheimer Society’s director of Advocacy and education, says that it wasn’t so long ago that people living with memory loss had to contend with a sense of shame.

“People kept it to themselves,” she says, noting that attitudes are changing in recent years. “We don’t always think about what it’s like for the person with dementia and their families. A lot of families don’t feel comfortable to share that diagnosis.”

Lindsey specifically touts the society’s First Link dementia support program, a hotline that connects people with dementia and their care partners to support services, education and information at any stage of the journey.

“Call us for any reason. If you are a person who is wondering about the disease or some symptoms that you might have, if you’re concerned about a family member, if you’re concerned about a friend ... please call us at the First Link dementia helpline at 1-800-936-6033,” she says. “Dementia is not a normal part of aging, so if you’re experiencing memory loss, or maybe a change in personality and you feel like something’s wrong, see your doctor.”

The Alzheimer’s Awareness Month open house in North Vancouver will showcase the work the Alzheimer Society does and how it supports the community.

The public is invited to the event at 212-1200 Lynn Valley Rd. on Jan. 30 from 3 to 5 p.m.

For Maynard, who’s grateful to be able to share more about his experience and highlight the work of the Alzheimer Society, he’s aware that all dementia or memory loss journeys are different, but what is similar is searching for those silver linings among the often trying times.

“She’s very content and smiley,” he says of his wife. “I took her for a walk yesterday and I was singing and she was whistling right along with me.”