The story is about love but we can’t start there, not just yet.

First we need the history.

George Orr was in Grade 8 when he reported a crime to his father.

My creepy old teacher, Orr told his dad, is fondling kids in class.

His father understood. After all, he’d been a student at Upper Canada College himself. And come to think of it, he remembered that teacher – the guy had been young back then. Still creepy, though.

“He was my teacher when I was there,” the father told his son. “Just don’t mind him.”

Don’t mind him.

On the other side of Toronto’s upper crust, James FitzGerald, recalled his teachers as: “a near-unbroken chain of brutes, bores and automatons.”

Between canings and a concept of sex that relied heavily on a science teacher’s sketch of the reproductive organs of possums, FitzGerald watched his father rocket to the top of the medical profession and then choke on the rarefied air.

“There was certainly pressure to go into the family business,” FitzGerald says. “In my family, the family business was suicide.”

The FitzGeralds were cold and ambitious and prone to addiction and madness, he says.

Speaking from Toronto, FitzGerald freely acknowledges his status as a privileged white male. But there’s more to be said on the subject, he insists.

“I’ve seen the dark side of privilege up close,” he adds.

FitzGerald’s new book Dreaming Sally is a novelistic memoir that recalls childhoods of privilege, the stirrings of the 1960s counterculture movement, an unlikely prophecy, and of course, a girl. Her name was Sally.

The book is scheduled to launch at Massy Books in Vancouver on Nov. 20.

While there were no physical barriers, Orr and FitzGerald essentially grew up in what was essentially a gated community. Their families had spent generations climbing in. Both boys wanted nothing better than to climb out.

Each of their grandfathers served as majors in the First World War. Both men enrolled their sons in Upper Canada College private school following the founding of successful businesses (an insurance company for the Orrs; a medical laboratory for the FitzGeralds).

In the next generation, Orr and FitzGerald served as naval officers in the Second World War, each stationed in the North Atlantic.

Both fathers entered the family business, albeit grudgingly. And they were both haunted by the choices they’d made.

“Our fathers were Irish-blooded addicts,” FitzGerald says.

The similarities continued in the third generation. Orr and FitzGerald each had younger brothers named Michael. Orr became a broadcaster and documentarian. FitzGerald found success as the author of non-fiction novels.

There is something unnerving, if not downright eerie, about the parallels.

“It’s weird,” Orr admits.

FitzGerald, Orr explains, chalks it up to some sort of synchronicity. “And I don’t,” Orr finishes.

“I’m fascinated by unconscious processes and synchronicity,” FitzGerald says.

On the surface, their personal histories fall into the category of “classical boomerology” FitzGerald says. But the parallel that may be most crucial, FitzGerald says, is the similarity between their two mothers.

Both Mrs. FitzGerald and Mrs. Orr went to the same school. Both had the misfortune to make all their major life choices before the arrival of the women’s liberation movement.

They were bright, ambitious, educated and stuck with the one job they weren’t suited for: motherhood.

They were beautiful, cold, and ultimately unable to attach to their children, FitzGerald says.

“The fathers had abdicated their role so the mothers were over-invested in us,” he says.

Each mother attempted to imbue her son with a drive to be conquerors of the establishment.

Instead, both boys wanted nothing better than to escape it. And like Andy Dufresne staring at that poster of Rita Hayworth, both boys found themselves looking to a beautiful girl as more than someone to love. For George and James, Sally was a means of deliverance.

“I think it helped explain why George and I were attracted to Sally in the first place,” FitzGerald muses. “Because she wasn’t like our mothers.”

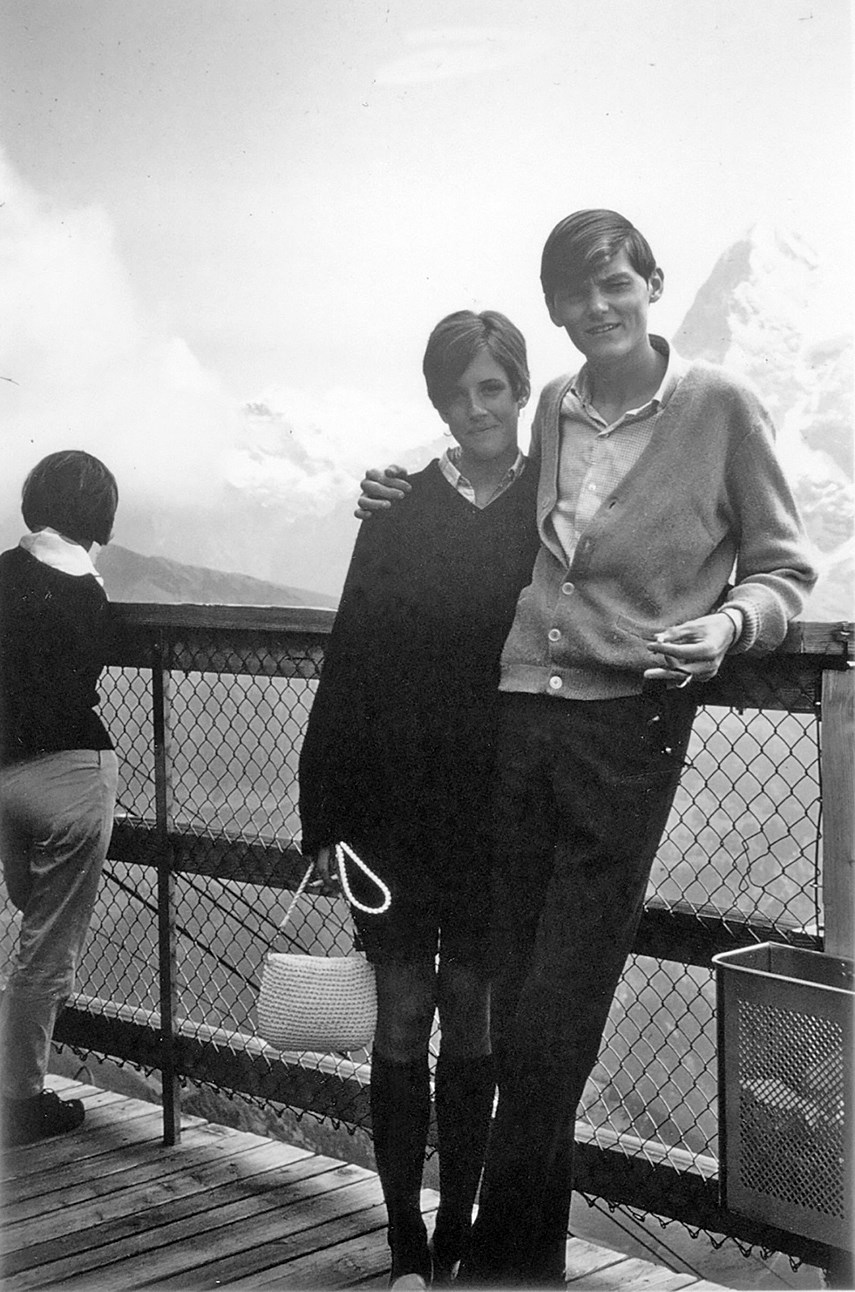

Physically, Sally seemed to have stepped right out of the Little Richard tune, “long and tall, like the song,” FitzGerald writes.

She was ribald and funny. In a love letter to Orr, Sally describes a bikini with a bow “right in the middle of my crotch.” Playfully, she adds: “And I’ll even let you pluck my bow.”

FitzGerald’s memoir describes Sally getting 86’d from churches over the length of her dress. He describes her laughing, her teasing. He reprints a letter where Sally boasts she could drink Orr under the table.

She wasn’t “smack-in-the-head gorgeous, but she radiated something exciting, something real, something alive,” he writes.

A large portion of FitzGerald’s book takes place when he, Sally, and two dozen other young Canadians toured Europe in the summer of 1968.

Orr was unofficially engaged to Sally. FitzGerald was unrequitedly in love with Sally.

FitzGerald recalls the tastes and sights and bonhomie of that trip. He writes about being next to Sally, putting his arm around her. Falling asleep next to her and tracing the contours of her face while wishing Orr would disappear from the planet.

Orr was stuck at home, lovesick and jealous, and brooding over something that was completely anathema to a rational young man with a proper education: prophecy.

Talking about it 50 years later, Orr takes a moment to collect his thoughts.

“I’m not the sort of person who’s ever had that sort of thing before or since,” he says. “But I knew, with a real clarity, this was going to happen.”

In August of 1968, Sally Wodehouse died following a bus crash.

“I knew she was going to die six months before she did, with some specificity,” Orr says.

He’d dreamed it and he’d told her. He’d told friends and family.

“I became a pariah,” he says. “Nobody wants to hear somebody say stuff like that.”

After Sally died, the reaction from Orr’s parents was silence and denial, FitzGerald says, discussing what he calls the upper middle-class WASP attempt to be, “more British than the British.”

Both FitzGerald and Orr were torn up by Sally’s death. But despite all their similarities, her death was the one thing that broke the parallels that joined them.

Orr put it behind him as best he could. But FitzGerald wouldn’t or couldn’t quite shed what he calls: “the ghost of Sally.”

“It was his first love,” Orr says. “This was going to be something he was going to mark his life by and so the drama, the tragedy, all that shit really stuck with him and stuck with him.”

But what made it a book, FitzGerald says, is when he found out about Orr’s dream.

“There would be no book without the dream.”

More than 40 years after they’d been in love with the same girl, FitzGerald and Orr sat face to face and talked about it all.

“I was very delicate and actually ambivalent and hesitant myself,” FitzGerald says.

“He was surgical as an interviewer and kind of heartless, but that was OK,” Orr says. “He didn’t ask questions with any concern as to how it would land on me emotionally. He just wanted to know data, reaction and frame of mind.”

“I kept saying, ‘We don’t have to do this,’” FitzGerald recalls. “He’d say: ‘Don’t apologize. I signed on for this so let’s keep going.’”

Never a fan of committee work, Orr rebuffed FitzGerald’s suggestion they co-write the book. Ultimately, Dreaming Sally is FitzGerald’s, although Orr’s phrases and recollections colour much of the story.

Today, Orr is married to the love of his life.

But his past, half a century later, is still alive inside him.

“I think unresolved trauma just makes a mess of your life,” he says.

Talking with FitzGerald was like therapy. “But I didn’t have to pay for it,” he adds.

Asked if it brought him closure, Orr is succinct. “No,” he says abruptly. “The notion that closure exists is something I think people got from Oprah Winfrey.”

FitzGerald concurs. There’s no cure or closure, he says.

But you can learn new responses, more creative ways of dealing with old trauma, he says. It’s what saved his life.

“That’s what saved my skin,” FitzGerald says. “Good old talk therapy and dreaming.”

But while there’s no closure, the book’s publication does mark an ending, Orr says.

“I’m just thankful it’s done. Fifty years,” he breathes.

Talking about the book and the experience, FitzGerald pauses a moment to consider one last question: What would Sally have thought about it all?

There’s class privilege, the graduation from “the childhood sandbar to the adult cocktail bar.” There’s dancing and fate and a song by the Box Tops that seems to follow FitzGerald and Sally from country to country.

What would she have thought?

FitzGerald considers another moment. “She might’ve said, ‘Lighten up, guys.’”