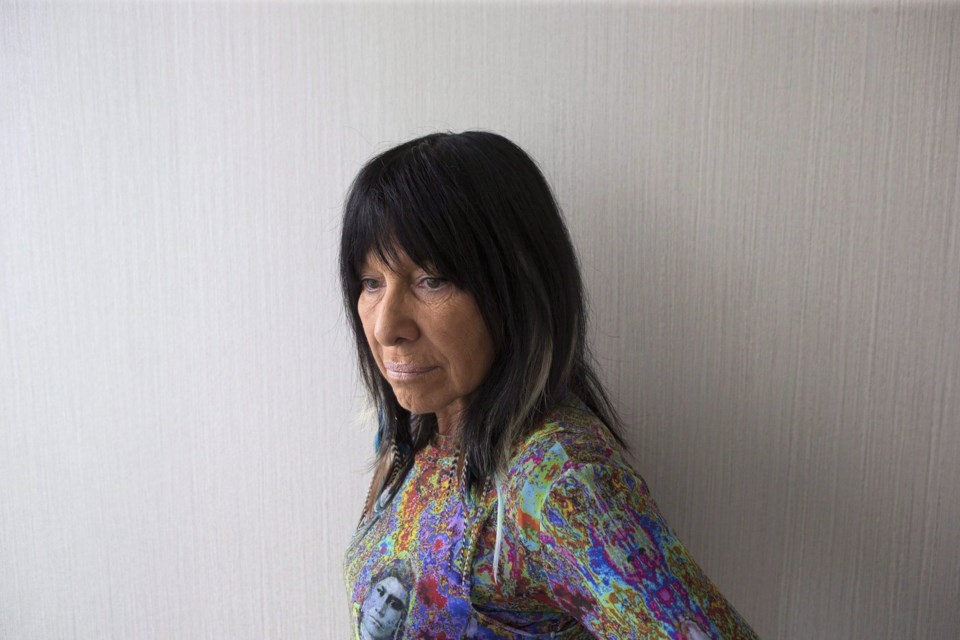

TORONTO — Buffy Sainte-Marie says she has returned her Order of Canada medals “with a good heart” and reasserts that she never lied about her identity, as more institutions deliberate what to do about the musician's many accolades in the absence of proof she was born in Canada.

In her first statement since she was stripped of the prestigious Canadian honour, the singer-songwriter said that she’s an American citizen and holds a U.S. passport, responding to questions around her birth and claim to Indigeneity by stating: "my Cree family adopted me forever and this will never change.”

She told The Canadian Press that she "made it completely clear" she was not Canadian to Rideau Hall, which bestows the national order, as well as to former prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau when he invited her to perform for Queen Elizabeth in 1977.

"It was very lovely to host the medals for awhile, but I return them with a good heart," she said in a statement provided Tuesday.

Her comments come as Rideau Hall confirmed it also terminated two jubilee medals given to Sainte-Marie in 2002 and 2012. Both were associated with her membership to the Order of Canada, which was awarded in 1997 and cancelled on Jan. 3 of this year.

Sainte-Marie lost the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal, which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the queen's ascension to the throne, as well as the Diamond Jubilee medal presented for the 60th anniversary, the government said.

Rideau Hall has declined to give a reason for their decision, saying they do not comment on the specifics of termination cases. The Governor General's website says non-Canadians are eligible for the Order of Canada "if their contributions have brought benefit or honour to Canadians or to Canada."

This all comes more than a year after a CBC news report questioned Sainte-Marie's Indigenous heritage.

The "Fifth Estate" investigative piece found a birth certificate that indicated she was born in 1941 in Massachusetts. The report cited U.S. family members who said she was not adopted and doesn't have Indigenous ancestry.

Sainte-Marie rose to fame as a folk performer in Toronto's Yorkville music scene, penning the war protest anthem "Universal Soldier" and later winning an Oscar as one of the songwriters on "Up Where We Belong," the ballad from the 1982 film "An Officer and a Gentleman."

All the while, she wove activism into her music and appearances and became a prominent Indigenous advocate on both sides of the border. Her efforts helped earn her a humanitarian award at the Junos in 2017.

Over her career, she collected an array of Canadian accolades, including a Gemini and the Governor General's Performing Arts Award.

In Tuesday's statement, Sainte-Marie expressed her "love and gratitude to Canada" and said she's "overwhelmingly grateful that I’ve been able to make my contribution."

But she didn't directly address whether she still believes herself to be of Indigenous descent.

Sainte-Marie has repeatedly described herself as First Nations from Canada, but adopted as a young child and raised in Massachusetts by Albert and Winifred Sainte-Marie. She has said Winifred identified as part Mi’kmaq.

Her 2018 authorized biography says there’s no official record of her birth. It says she was probably born Cree on Piapot First Nation in the Qu’Appelle Valley in Saskatchewan in the early 1940s. Named Beverley, she was nicknamed Buffy in high school.

Her new statement says she's "lived with uncertainty" about her parentage and where she was born.

"I’ve never treated my citizenship as a secret and most of my friends and relatives in Canada have known I’m American, and it’s never been an issue. Although it’s true that I’ve never been certain of where I was born, and did investigate the possibility that I may have been born in Canada, I still don’t know."

Sainte-Marie also challenged the assertions made in the CBC investigative report, which she also did after its 2023 release.

"They didn’t interview anybody who knew me or my growing-up mother but instead constructed a false narrative and then asked people to comment on it," she said in her new statement.

CBC spokesperson Chuck Thompson said that the broadcaster stands by its investigative story.

Several Canadian institutions that bestowed honours on the acclaimed musician are grappling with how to proceed.

Sainte-Marie was recently scrubbed from an exhibit at Winnipeg's Canadian Museum for Human Rights titled "human rights defenders.”

The University of Toronto says it has received a petition to de-recognize an honorary Doctor of Laws degree given to her in 2019 but has yet to make a decision.

Some of the country's music organizations say they're reconsidering the status of Sainte-Marie's past honours.

Allan Reid, the head of the Junos, said last month that internal discussions are ongoing with its Indigenous Music Advisory Committee, which is reviewing the five music awards she has won over the years. Sainte-Marie is also an inductee in the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.

Similar conversations are being had behind the scenes at the Polaris Music Prize, which named Sainte-Marie’s 2015 album “Power in the Blood” the winner of its $50,000 award that year.

"If some Canadians now want to reject me, okay," Sainte-Marie said in her statement.

"People in Canada have been so nice to me, particularly the arts community, and I’ve been so honored by this acceptance, I have truly felt 'adopted' by Canada although I can see today that not everybody in Canada sees it that way."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 4, 2025.

David Friend, The Canadian Press