Trees are a defining feature of the North Shore. They help to cool the surface temperature, and absorb water as it runs down slopes and off asphalt surfaces.

Those points were raised at District of North Vancouver chambers on Oct. 7, as council voted unanimously to update policy so that it includes an urban forest management plan. The successful motion also directed staff to create tree-planting requirements for new developments.

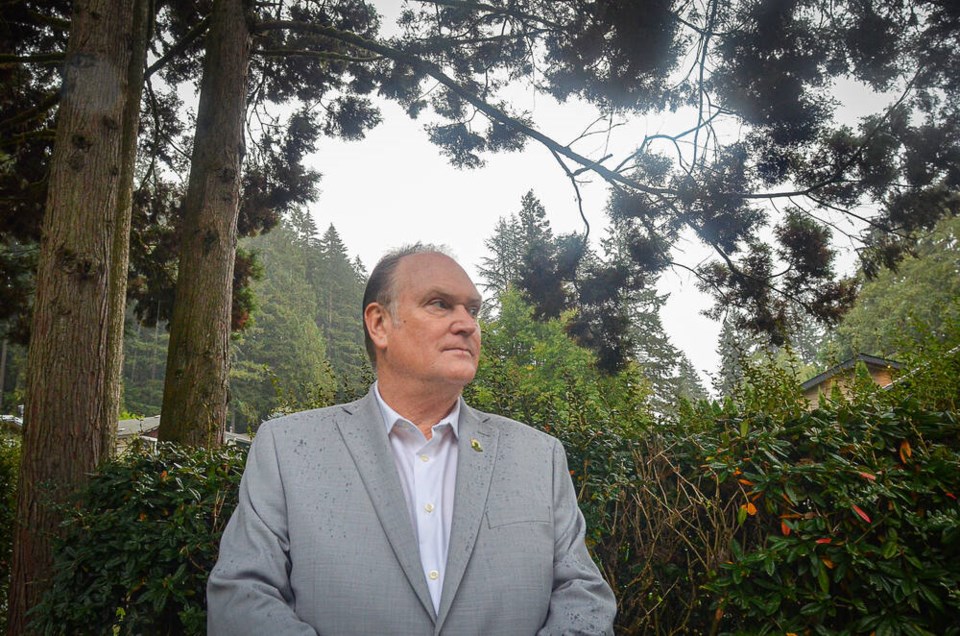

But having too many trees in residential neighbourhoods can create wildfire risks, so the district should be careful when it adds more protections, said Mayor Mike Little.

Part of the inspiration for the protection plan is a new report from Metro Vancouver that shows the urban tree canopy being cut back. In 2020, total tree canopy across 21 neighbouring municipalities was 31 per cent, down one per cent from 2014.

Over the same period, impervious surfaces like roads increased to 54 per cent from 50 per cent.

“Impervious surfaces are associated with higher temperatures, increased flood risk and poor water quality,” reads the study.

According to North Van District staff, tree canopy provides shade and natural habitat, while capturing stormwater. With global temperatures rising, urban trees are “essential” to maintain a livable environment for residents, staff said in a report to council.

And with new provincial legislation to up density in residential areas, tree canopy will continue to fall if measures aren’t taken to protect it, staff said.

'It’s a full picture of forestation, not just trees around homes'

Coun. Lisa Muri said the Metro study gave her concerns along with recent trends in development.

“Especially in the upper Capilano, Upper Lonsdale area, a significant amount of redevelopment is going from ranchers that were built in the 1950s … from a 1,500- or 2,000-square-foot rancher and replacing it in some cases with houses that are 10,000 square feet and above,” she said.

We’ve seen a lot of outrage in the community when we lose big [trees], especially big firs and cedars that sit in the middle of a lot that are cut down because somebody bought a lot they now want to redevelop,” Muri said. “And many of the new properties that are being built, the surface doesn’t allow drainage.”

Coun. Jim Hanson said the point of the motion is to contemplate if there are more strategies to better protect trees, even if the community is adding more housing.

“Are there policy initiatives that can be used to better create new green spaces or plant trees in areas that perhaps are available to us for that purpose, so that we can tilt the balance back towards more tree cover instead of less?” he said.

While it’s hard to find anyone in the district who isn’t inspired by trees, Little expressed his “unpopular opinion” that too many green giants ought not to grow close to homes.

“We are the biggest risk for a devastating, catastrophic forest fire,” he said. “If you have trees in and around your houses, you increase the risk that a forest fire will be a house fire, and that a house fire will be a forest fire.”

“While I applaud the goal to retain trees throughout our community for all of the natural benefits that are self evident in there, I do think that the right place for most of them is on our public lands,” he added.

Little said he’s very cautious when it comes to bringing in additional regulations to force the retention of trees.

“We hold up our forest, like it’s the hero, like it’s this wonderful thing, and that’s awesome,” he said. “But when Lytton happens, I hope that we would have the safety measures in place …. to protect the most defensible space for our fire departments to be able to react.”

But Hanson emphasized that it’s not just trees on private property that are the subject of concern.

“It’s also the public lands, and specifically in the Metro report, it was interesting because they identify the North Shore as an area where there is open space on public land that would potentially be available for planting,” he said.

“It’s a full picture of forestation, not just trees around homes,” Hanson said.