She was there at the top of the family tree, but there was only one problem – her birth name was missing.

This didn’t sit well with North Vancouver writer and artist Jenn Ashton.

“We thought that odd,” she says. “That bothered me because a lot of our family history was erased.”

Decades after Ashton’s uncle first took up the task of piecing together more of the family’s history – including their relation to local First Nations – Ashton took up the mantle of putting together one of the final pieces.

After three years of research for a book she was writing on her family’s history and the origins of Vancouver, Ashton had ascertained that her third great-grandmother (or, her great-great-great-grandmother) had been given the name Celestine, had been born in X̱wáýx̱way, now known as Stanley Park, and was from Squamish Nation. She was likely born around 1844 and lived to be almost 100.

But what had been her birth name?

That question continued to elude Ashton until, seemingly all of sudden, everything fell into place.

The story of how Ashton learned more about her relative, including that her birth name was Siamelaht, is recounted in an article published last year in British Columbia History magazine.

Last week, the British Columbia Historical Federation announced that Ashton’s article had received an honourable mention for its contribution to enhancing knowledge of the history of British Columbia.

Like any good piece of history, Ashton’s narrative twists and turns, hits roadblocks and misdirects, until finally arriving at something akin to clarity. There’s also an awesome surprise which really ties everything together.

She recounts a weekend spent researching her family history, during which an online archive opened its doors for a limited, subscription-free period, and ultimately, propelled the project forward.

“I awaited the turn of the clock, and then was in the virtual door so quickly, I’m sure I was the first inside, my heart pounding like it was the Army & Navy shoe sale,” writes Ashton.

She searches and examines and searches some more. Suddenly, she finds a match.

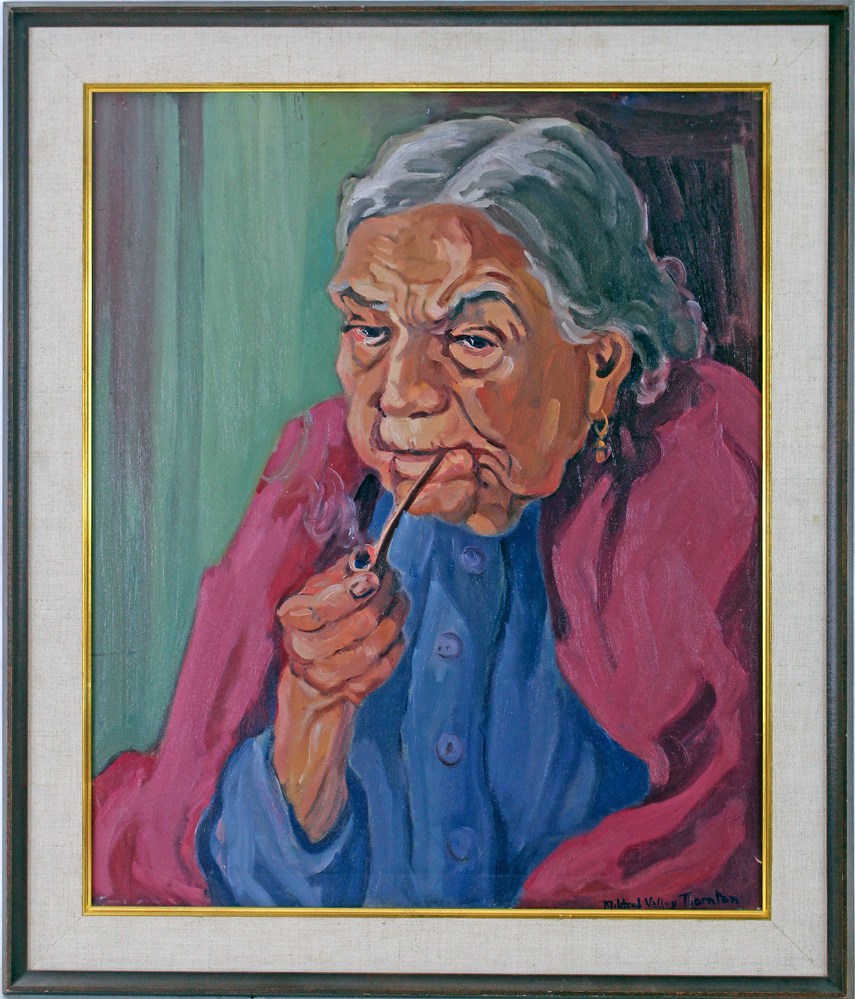

In a full-page Vancouver Sun article dated March 7, 1942, a well-known B.C. portrait artist named Mildred Valley Thornton, who was particularly known for her paintings of Indigenous people, had written a story detailing Celestine as she approached her centenary.

The article was subtitled “Age Brought Dignity and Peace To This Child of the Squamish.” In the old newspaper article, Thornton refers to her as “Siamelaht,” her Squamish name at birth.

The newspaper article also featured a giant portrait that Thornton had painted of Siamelaht. That same painting now graces the magazine cover of the publication that contains Ashton’s award-winning article.

“I started finding other articles about her in the newspaper. It turns out she was kind of somebody at that time,” says Ashton. “It was a very important part of Vancouver’s history.”

Of the many insights gleamed about the woman’s life throughout the course of Ashton’s article, one of many that stands out is that Siamelaht “could easily remember when there were no white people.”

And while Ashton set out to write her article as a means to bringing life to an important, often tumultuous and appalling period of Canadian history, it was also about forming a solid anchor for herself and her present-day family. It’s been enlivening to know more about where she came from, she says.

“It felt deeply disrespectful to her memory that we didn’t even know her name,” says Ashton. “Now I’ve met so many people who I’m related to. I have cousins all over the North Shore.”

And the twist in Ashton’s article is surely too serendipitous not to share.

Twenty years ago, she writes, Ashton and her daughter were at a garage sale where they bought a packet containing 30 antique postcards, many containing reproductions of B.C. paintings. She held onto the postcards for decades.

Last year, when Ashton was researching for her article and finally happened upon the painting of Siamelaht while searching through the archives, something about the image jumped out at her. She’d seen the image before. As the painting stared back at her, she realized that in many ways she’d already known her old relative for decades: Thornton’s painting of Siamelaht had been turned into one of the postcards that Ashton was already in possession of.

“I’ve been looking at her picture for decades without knowing who she was.”