Warning: This story contains details that may be distressing to some readers.

The mystery of two children found brutally murdered in Vancouver's Stanley Park nearly a century ago is one of the city's oldest unsolved crimes.

The Babes in the Woods case has something of a Hansel and Gretel mythology around it.

And what makes the case more compelling is the fact that British Columbia serial killer Clifford Robert Olson's mother was a tipster to the police in the case.

Brothers Derek and David D'Alton, aged six and seven, were believed to have been killed in 1948. Their skeletal remains went undiscovered until 1953, when a groundskeeper clearing brush found them near Beaver Lake.

Stepping through the brush, Albert Tong came across a patch of leaves that made a strange crunching sound. Digging beneath the brush, he found numerous bones embedded in several years worth of earth and decaying leaves.

It was the boys' remains.

They had been bludgeoned with a hatchet, which was found nearby, and were lying in a straight line with the soles of their feet facing each other. A woman's fire coat covered their bodies. Also found at the scene was a woman's shoe, some children's clothing, a lunch box and a leather aviator's cap.

Lots of theories, few clues

In the decades that followed the grisly discovery, many theories about who the children were — and who may have murdered them — fascinated locals and stumped investigators.

One theory was that the children were of Madeline Fortier from Levi, Que., who came forward to tell police she had given her children up for adoption in Vancouver. At one point, there was speculation that a woman may have killed the children before plunging to her death near the Lions Gate Bridge.

Alleged witnesses also came forward with tales of sightings before the crime.

One spoke of seeing a coatless woman with one shoe carrying a hatchet. Another saw a woman with a hatchet entering the park with two children who looked “either Swedish or Norwegian.” Other witnesses spoke of a woman with blood on a shoe accompanied by a nervous man.

There were also reported disappearances of a couple with two boys from a downtown rooming house. Another tip came from a young boy about two friends he made that he never saw again. He reported being brushed off when he saw their mother and asked about his friends.

Police piece together clues

Evidence from the scene proved to be fruitless.

An Eaton's department store manager was able to identify the Fraser clan tartan jacket worn by one of the boys, while a shoe was also identified by its maker. A Vancouver furrier recreated a reproduction of the fur coat, in an attempt to jog memories. So too were replicas of the children's heads and faces.

Despite this, questions arising from the discovery were further stymied by the fact that a medical examiner had decided one child was male, the other female.

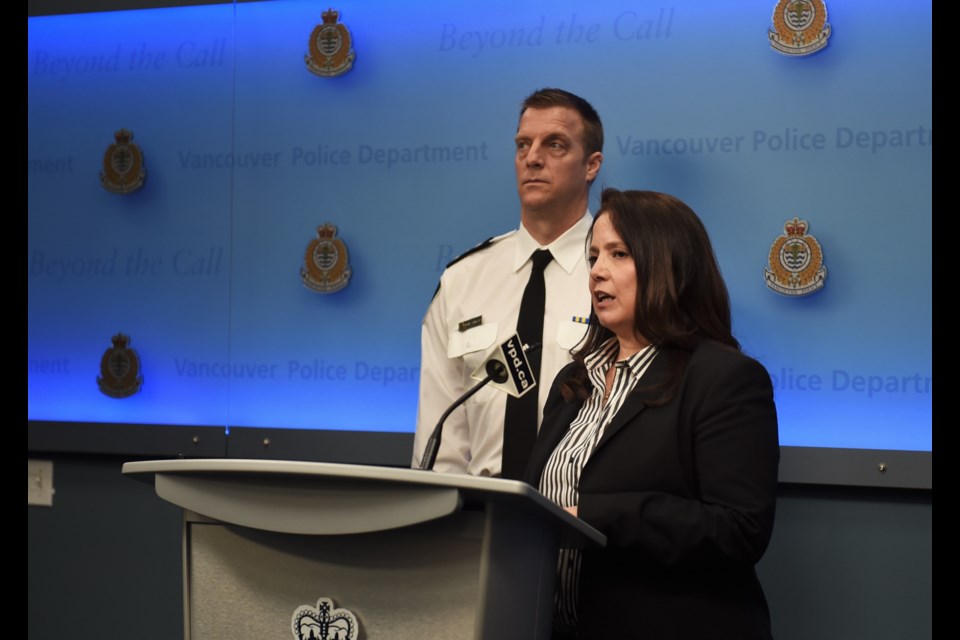

This misidentification certainly hampered the work of early investigator Don McKay, who may have been able to close the case if he was on the lookout for two missing boys, says Brian Honeybourne, who took up the cold case in 1996.

It was Honeybourne who had a forensic dentist, Dr. David Sweet, use dental DNA to establish the children were both boys.

He retired in 2001, after putting in hundreds of hours of overtime to try to solve the case.

Giving the boys a name

In 2021, investigators used DNA from the boys' skulls and contracted Redgrave Research Forensic Services, a Massachusetts-based forensic genetic genealogist company, to help.

The company identified the maternal grandparents of one of the boys and built out a family tree using DNA submitted to private companies for genetic testing.

Once the match was made, investigators were able to locate family members and check school records. That led them to a distant relative living in Metro Vancouver.

Derek and David were believed to be descendants of Russian immigrants and lived in Vancouver with family living near the entrance of Stanley Park.

The person believed to have killed them was likely an unnamed, close relative who died 25 years ago.

Murder on display

At one point, the boys' remains were on display at Vancouver's police museum until replicas took their places. Their skulls were also put on display for a time at the Pacific National Exhibition.

Since then, their remains have been cremated, the ashes scattered in the waters off Vancouver's Kitsilano Point. Finally, at rest and known.