For expats or immigrants, the emotional journey of shifting a life across the world and understanding the new and ever-changing meaning of ‘home’ can be difficult to put into words.

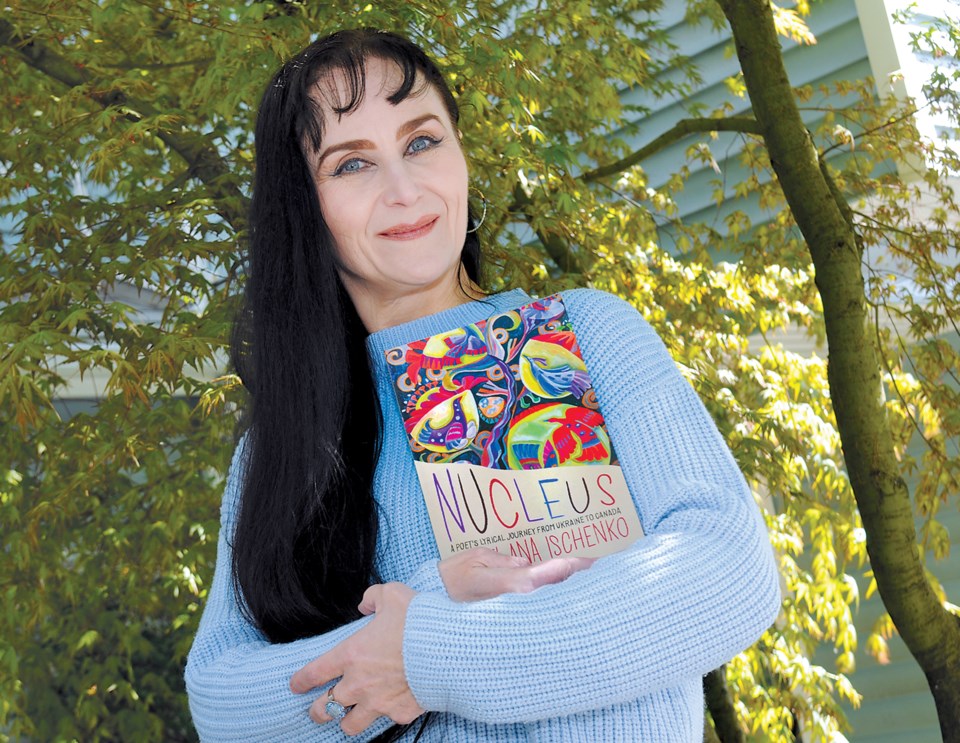

Yet for Svetlana Ischenko, a North Vancouver poet, playwright and teacher, words are what come easily.

In Nucleus: A poet’s lyrical journey from Ukraine to Canada, Ischenko pulls from 23 years of living abroad, detailing the waves of excitement, homesickness and frustration that comes with moving from the city of Mykolaiv to Canada’s North Vancouver.

“I wrote the very first sonnet at the beginning, when I emigrated in August 2001,” she said. “The rest just follows naturally, it explains my transition from being totally Ukrainian, to becoming a Ukrainian Canadian, and then, eventually, to becoming Canadian.”

The title Nucleus references all the separate elements that can combine to make up a person, said Ischenko. When moving abroad, a person doesn’t stop being one thing to become another, but instead becomes a mixture of the cultures that surround them.

“You don’t lose your identity, you are who you are,” she said. “You actually become a Canadian and you gain more. You add to your Ukrainian identity, and that nucleus grows as you absorb and learn here in Canada. That becomes you.”

Anyone who has ever tackled the challenge of moving abroad will likely find solace and humour in Ischenko’s verses. One particular favourite of the poet’s, simply entitled home, addresses conversations so often had between new acquaintances and those no longer living on home soil.

It starts:

“Where are you from?”

– “South of Ukraine, Mykolaiv…. it’s near Odessa… north of the Black Sea…”

“M-m-m… Is it a part of Russia?”

– “No, it’s Ukraine.”

“Was it a Soviet Union sort of thing?”

– “Yeah, sort of…”

Later on, it reads:

“I’ve noticed, you have an accent. Definitely eastern European. Polish?”

– “Ukrainian.”

“What nationality are you?”

– “Canadian.”

The poem is the essence of the book, said Ischenko. An answer to all the questions others may have and even the complex queries that have arisen within herself over the years. With each stanza written, Ischenko tackles her own question of what it means to be both Ukrainian and someone who is enamoured with their adopted country.

Correlating with her own 23-year journey, the first section of the book was written in Ukrainian, the second and third in a mixture of English and Ukrainian and the fourth, when Ischenko had grasped her new tongue, was written in English. While the majority was transcribed for the final edition of Nucleus, marking her first English language published set of works, Ukrainian words are still interspersed.

“For some of the words there is not a direct translation, and to change them completely would be to lose their essence and their meaning,” she said. “There are a bunch of explanations at the end of the book of all the terms that I used in Ukrainian, because this should still have Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian sensibilities.”

The poems have gained new poignancy in light of the unfolding events in Ischenko’s war-ravaged home country. Oftentimes they reference the culture, traditions and land of the country she grew up in, long before her family were plunged into omnipresent danger and her friends were forced to fight on the frontlines.

The current situation in Ukraine is a topic likely to arise at Nucleus’ book launch April 14, due to be held at West 1st Street’s Helicon Books. Ischenko said she welcomes all questions on her home, both new and old.

Mina Kerr-Lazenby is the North Shore News’ Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.