Storm arrived with late December’s heavy snow, high winds and frigid temperatures.

The four-pound giant Pacific octopus was stranded at Vancouver International Airport after her flight to Finland was cancelled.

When no other flights were available for a week, the Vancouver Aquarium asked the Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea if it could care for her.

And Finland’s loss has become Sidney’s new star attraction.

“The aquarium was really close to releasing Sequin, our previous octopus, so we said we would love to give her a home. So instead of getting on a flight, she hopped on a ferry and came over here and now she will live with us for six months,” said senior aquarium biologist Amanda LeSergent.

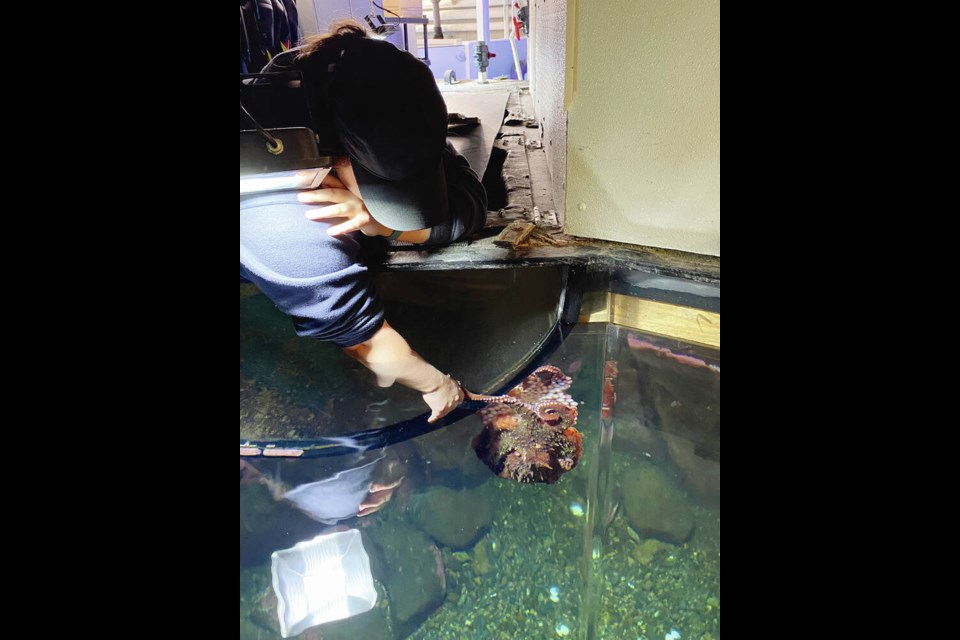

On Wednesday, Storm was snoozing, suckered up against the glass of her floor-to-ceiling tank. “She had a snack yesterday so she may not be interested in playing,” LeSergent said, as she tried to get Storm’s attention with an orange toy.

The giant Pacific Octopus is the biggest octopus species in the world and they grow quickly, which means they do a lot of sleeping, she said. “They tend to sleep for 24 to 48 hours after we feed them, depending on how big the meal was. So if she had a really big crab, she might sleep for two or three days.”

Storm uncurled a tentacle and gently explored LeSergent’s hand. But it was too much effort and the octopus retracted her arm and slid sleepily down the glass.

Aquarium staff believe Storm is a girl.

“We’re 99 per cent sure but it’s actually really difficult to tell when they’re small, because the way you figure it out is their third arm from their right eyeball. If they have suckers all the way down to the end of their arm, they’re a girl. If they’re missing the last couple of centimetres, they’re a boy,” said LeSergent.

The biologist can’t tell how old Storm is. Octopus size depends solely on how much they’ve been eating, she explained.

“She could be really old and not have eaten that many crabs, or she could be really young and have had an abundance of food when she was little,” said LeSergent. “The last octopus we released was 26 pounds, so they can grow quite a bit in their time here.”

Storm was captured in Ucluelet and will be released there in May or June by aquarium staff. One reason is they get too big for the aquarium, said LeSergent. Another is that an octopus only reproduces once and they want that to happen in the ocean.

Octopuses are incredibly smart. The aquarium tries to keep their brains active because they need to hunt when they are released to their natural environment.

During the first couple of months, a live crab is put on the bottom of the tank for the octopus to hunt. Then a crab is put in a jar without the lid so the octopus gets used to the jar. Then a crab is put in a jar with a lid.

“We kind of show them that the lid comes off. Eventually, they twist or rip the lid right off.”

And it’s not just one brain. An octopus has nine brains in total, said LeSergent. Each arm has its own mini-brain and can think independently without notifying the main brain.

One arm can check things out with touch, taste and feel. If it finds something interesting, the arm can signal the two arms beside it. Those two arms will also check things out, so there will be three arms total on something. If the three arms find it’s still interesting, they will let the main brain know, said LeSergent.

“So many people just don’t get to see octopus and see how they move and how they think. Storm’s kind of like our little ambassador. She gives people that connection with the ocean that you don’t get from the surface. For us, as a smaller aquarium, the octopus is kind of our highlight.”

Neither LeSergent nor Kit Thornton, head of animal care, know if Finland has received a replacement octopus yet.

In Ucluelet, octopuses are sourced by a marine biologist company licensed by Fisheries and Oceans and Environment Canada. The company follows provincial and federal laws as well as the laws of the importing country, said Thornton. Shipping octopuses internationally is allowed, with a stringent permitting process, she said.

The two say the best part of their job is releasing the octopus into the ocean. LeSergent and Thornton go into the water with their charge.

“We have a bucket with holes in it and they sit in the bucket and we take them out to an appropriate area that they would like to live in and we tip the bucket and wait for them to do their thing and follow them around to make sure they are happy. It kind of eases the sadness,” said LeSergent.

With a previous release,“I dived down for a last look and he reached out and touched me again,” said Thornton. “I was so excited, I screamed into my mask. That was really special.”

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]