A patch of North Shore waterfront spotlighted as one of the most hazard-prone pieces of land in Metro Vancouver is facing new scrutiny as the prospect of disaster collides with plans to expand housing and extend the life of a major chemical plant.

East of the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing, the tract of reclaimed industrial land is in the same area where the District of North Vancouver plans to build more than 1,000 residential units in a bid to help alleviate its housing crunch.

It’s also where the multinational chemical company Chemtrade Logistics Inc. is pushing to extend the life of a potentially risky chlorine gas plant.

John Clague, a professor and former director of Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Natural Hazards Research, said newly released hazard maps from the Metro Vancouver regional government represent a first pass at understanding risk in the region.

And while he cautioned against directly using them for land-use planning, they do offer a “reasonable view” of the multiple hazards facing the public.

“I think that these areas are hazardous … people ought to be aware,” Clague said.

The analysis, carried out by Ebbwater Consulting and recently presented to Metro Vancouver’s board, warns hazard-prone areas “should be avoided for the siting of critical infrastructure, or high-density residential or commercial zoning.”

The maps paint a picture of areas most prone to wildfire, floods and earthquakes. They don’t measure the vulnerability of buildings, infrastructure or communities that stand in the way.

It’s also not clear how the expansion of housing or the extension of Western Canada’s largest producer of chlorine could raise risk along a rapidly developing section of North Shore waterfront.

Housing, industry see possible collision with hazards

Chemtrade Logistics Inc.’s North Shore plant produces 70 per cent of B.C. and Alberta’s chlorine supply — a substance used to disinfect pools and bleach paper, but at high doses, can be deadly to humans as it supercharges fire or is vaporized in the air.

The company’s current agreement would halt its liquid chlorine operations by July 2030. To head off that potential blow to business, the chemical company is in negotiations with the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority to extend its operating permits while targeting several elected officials in a lobbying campaign to back that effort.

While Chemtrade has a strong safety record, high-cost accidents involving chlorine have happened in other parts of the world in recent years, and some in the community have raised questions over potential fallout in an emergency.

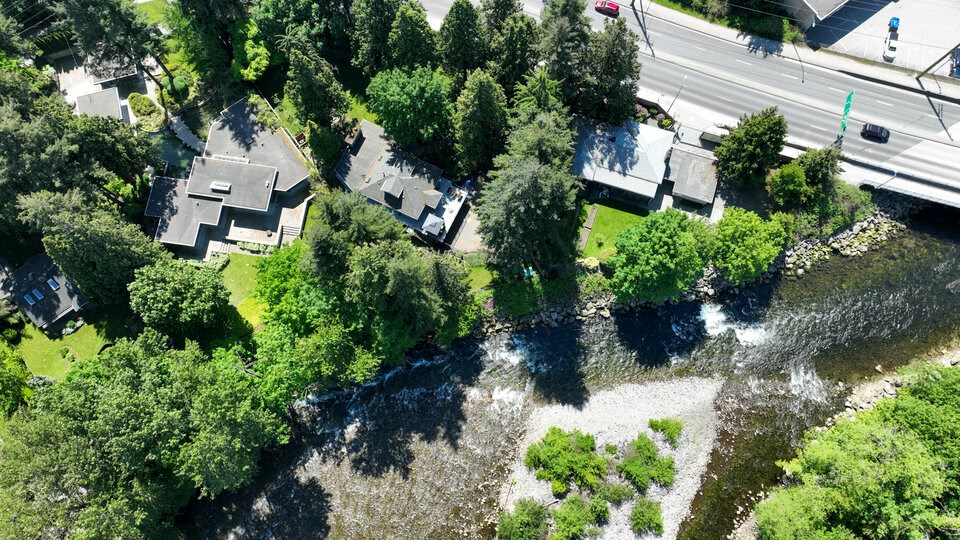

Less than a 150 metres to the west sits the North Shore Recycling and Waste Centre. An elementary school and preschool are only slightly to the north. Existing homes and businesses are expected to balloon in the coming years.

Less than a kilometre to the north of the chlorine facility, the District of North Vancouver has staked the Maplewood area as the future site of 1,500 residential units. They will form the backbone of one of four future town hubs slated to account for 75 to 90 per cent of new residential units in the district by 2030, according to the Official Community Plan (OCP).

The district’s community plan makes room to “maintain and enhance light industrial uses” but nowhere in the OCP does it outline the risks associated with a potential collision between residential neighbourhoods, a chlorine facility and the sudden onset of a wildfire, earthquake or flooding.

The potential for disaster at the chlorine plant and storage facility has already raised concerns with local residents. The planned construction of a new residential hub for the North Shore raises the stakes even more.

“Those tracks run all along the shoreline, so any onshore wind … could carry that up the mountain, so to speak, into the residential neighbourhoods,” said Graham Gilley, chair of the Windsor Secondary parent advisory committee.

Gilley, who toured the Chemtrade facility as the former director of enterprise risk management at Mulgrave School, said he was unaware of the company’s move to renegotiate its lease.

“People will want to know about the measures in place to protect the public,” he said.

A spokesperson for Chemtrade said the company has reduced the amount of liquid chlorine stored on site by 96 per cent since 2000 and invested $500 million into the plant since 2010.

But according to Doug McCutcheon, a professional engineer who has reviewed Chemtrade’s risk assessments on behalf of the district, the company is unlikely to substantially reduce risk at the plant because it would likely drive up chlorine costs.

“My bet is that they would not do that,” McCutcheon said.

The District of North Vancouver has long built the risks of fires, floods and earthquakes into its planning process, according to Mayor Mike Little.

He said his biggest concern was earthquakes and whether infrastructure is hardened enough to survive a disaster and still function during recovery.

More than Maplewood, Little said he’s worried about Cleveland and Seymour dams failing, or the Lions Gate Wastewater Treatment Plant going offline — a facility located in a second hazard-prone hot spot identified in the Metro maps.

Much of the North Shore sits on granite bedrock, but sections of the Maplewood and Norgate areas east of the two bridges are built on sediment and artificial fill more prone to damage from earthquakes.

One of the highest risks, acknowledged Little, is liquefaction — a phenomenon where water-logged ground starts to act like a liquid, cracking foundations, triggering landslides, and even swallowing up buildings and cars.

SFU’s Clague says much of the strategic infrastructure in Metro Vancouver has already been built on ground prone to failure. He pointed to the port in Delta, Vancouver International Airport and transmission lines crossing the Strait of Georgia.

“The cow’s out of the barn as they say,” Clague said.

Whether or not the two hazard-prone areas on the North Shore would deepen that trend remains up for debate.

Questioned over Metro’s latest hazard maps, Little said it is worth a second look at whether the district should continue to plan for future density in Maplewood, especially at a time when the province is imposing new housing targets and zoning rules on top of municipalities’ planning processes.

“I think it's absolutely reasonable for us to go back and look at the risk and see how that lines up with our plans,” said the mayor, “to see what aspects of risk can be mitigated and what just simply can't be.”

‘Might seem scary’ but knowledge spurs action

The North Shore is not the only area in Metro Vancouver identified as being particularly prone to natural and climate hazards.

Under extreme but lower probability scenarios, flooding, fires and earthquakes threaten areas along the Pitt River and the Fraser River — including the Fraser's mouth and shoreline stretching from Coquitlam to Maple Ridge and Langley Township.

The land of the Squamish, Katzie and Kwikwetlem First Nations all fall in areas highly prone to multiple hazards.

More extreme but less frequent hazards also threaten large swaths of Delta, Surrey and Richmond, zones primarily vulnerable to floods and earthquakes.

Glacier Media contacted 15 of the largest and most hazard-prone Metro Vancouver jurisdictions identified in the maps. Three said they did not have time to answer questions by the time of publication, and five did not respond at all — including Pitt Meadows, one of the most flood hazard-prone cities in the region.

Some authorities appeared to be further behind in developing plans to adapt to climate and natural hazards. Pardeep Purewal of the City of Maple Ridge said the municipality is still working on a climate action plan to find ways to protect the city, with public engagement set to “begin shortly” and will later incorporate Ebbwater’s maps.

Another area the maps identify as especially prone to flooding is the mouth of the Coquitlam River. The City of Coquitlam did not respond to questions. But Trisha Maciejko, Port Coquitlam’s emergency preparedness manager, said city staff will review and consider the maps as part of their work to improve its hazard, risk and vulnerability assessment.

Staff from Vancouver, Surrey, Richmond and New Westminster, meanwhile, all said they had already identified the risks shown on the multi-hazard maps or would be incorporating them into upcoming emergency plans.

The regional hazard maps will help cities “better understand risk and common interests across the region,” including “critical infrastructure vulnerability,” said Angela Danyluk, manager of climate adaptation and equity at the City of Vancouver.

City of Richmond spokesperson Clay Adams said the municipality “already has one of the most comprehensive flood protection systems in British Columbia” — one that can handle a one-in-500-year flooding event. He said the latest maps will help refine strategies already underway.

Other groups tasked with protecting the public were more explicit. Emily Dicken, director of the tri-municipal preparedness and response agency North Shore Emergency Management, said the Ebbwater report did not surprise her.

“This is something that I think about probably 24/7 and way more than I should,” she said.

But when it came to the public, she said the maps could galvanize people to act.

“Even though this information might seem overwhelming, and in some ways that might seem scary, we know that people will not usually take action towards preparedness and readiness if they do not know their hazards,” she said.

“Knowing your hazard is the first step of becoming prepared.”

Metro Vancouver told the authors of the Ebbwater report not to speak to media, and instead direct all press inquiries to the regional body. In an interview, Metro senior planner Edward Nichol said the maps helped the regional body understand where multiple hazards overlap. He did not comment on the most hazard-prone areas.

Maps come with limits

Collecting all the hazard data and sewing it together into maps must have taken a “colossal effort,” according to Tamsin Mills, a former planner with the District of Squamish and the City of Vancouver.

Like other experts interviewed for this story, Mills warned the maps come with a number of caveats.

She said the maps don't indicate overlapping hazards will happen at the same time, or that once vulnerability studies are carried out, other areas of the Metro region might not light up red.

“Maybe an older building in Richmond in a liquefaction hazard area is of way greater concern than an older building in that dark coloured area of North Van,” said Mills, now a senior associate with Pinna Sustainability. “We don't know. This map is not telling us that.”

Ebbwater produced earthquake hazard maps modelling M4.9 and M7 quakes in the Georgia Strait. And whereas wildfire and flood hazard information was pulled from provincial and regional databases, the authors did not consider dike breach scenarios due to inconsistent information from cities across the region.

Overall, the quality of data available for the report was patchy as some municipalities denied access to certain sensitive information due to perceived conflicts or risks, the report said.

Insurance companies hold ‘black box’ of disaster data

Rob de Pruis, the Insurance Bureau of Canada’s national director of consumer and industry relations, said the maps offer a good starting place to build understanding, but they don’t come close to the detailed risk maps insurance companies rely on.

Those subscription-only maps can cost millions of dollars and are not accessible to the public, de Pruis said. He said revealing them would be like asking Coca-Cola to give away its secret formula to the public. It would affect companies’ competitive advantage, and in turn, stock and share prices.

Mills said infrastructure owners are equally nervous. When she would meet with them as a planner for the City of Vancouver, they would be reluctant to put marks on a map and reveal vulnerabilities to flood hazards. The fear, she said, was that it would reveal a soft spot that could be used in a cyber or terrorist attack.

For local governments, detailed hazard maps could also expose municipalities to lawsuits claiming a city knew about the risks and chose to do nothing, said de Pruis.

Then there’s the potential risk to property owners: if maps show the public certain properties are in a high-hazard area, it could impact property values.

All those factors combine to put a chilling effect on the public flow of disaster information, agreed Mills and de Pruis. Ultimately, the public is kept in the dark.

The latest set of hazard maps produced for Metro Vancouver represents an attempt by experts and government to play catch up with the insurance industry but in a more transparent way.

“This is a great first step. But it's just that first step,” de Pruis said.

Balancing housing and hazards

Like much of the Metro region, Clague said the North Shore has seen “phenomenal” growth in recent years. Largely but not solely focused along major transportation corridors, that growth has also come up against local opposition in a region with limited space to build.

“You can imagine what would happen if they started to build SkyTrain and highrises all over West Vancouver,” said Clague. “We're caught between a rock and a hard place.”

Mills said the latest Metro hazard maps should put pressure on city, regional and provincial governments to show the public they are balancing a race to build affordable housing with long-term safety from disaster.

The maps also suggest the province may need to come up with alternatives when it pushes for urban density that doesn’t make sense in some hazard-prone places, she said.

“Let's consider hazards as well as affordability,” said Mills. “I don't think that has been done well.”

“Clearly, this should give pause.”