Seismic activity recently pinpointed to the lunar south pole is symptomatic of something bigger — the moon is shrinking, a new study has found.

Over the last few hundred million years, the core of the natural satellite has cooled, leading to the formation of faults, moonquakes and landslides as the lunar surface buckles inward. As its surface deforms, the moon’s circumference has shrunk nearly 50 metres, say researchers in a study published in the Planetary Science Journal last week.

The study, co-authored by Catherine Johnson, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, adds to a growing body of evidence that the moon is more seismically active than once thought.

Gordon Osinski, a professor in the University of Western Ontario’s Department of Earth Sciences, said the findings could pose a threat to lunar outposts planned as part of an upcoming series of crewed moon missions.

“I think the biggest implication is for permanent structures,” said Osinski in an email.

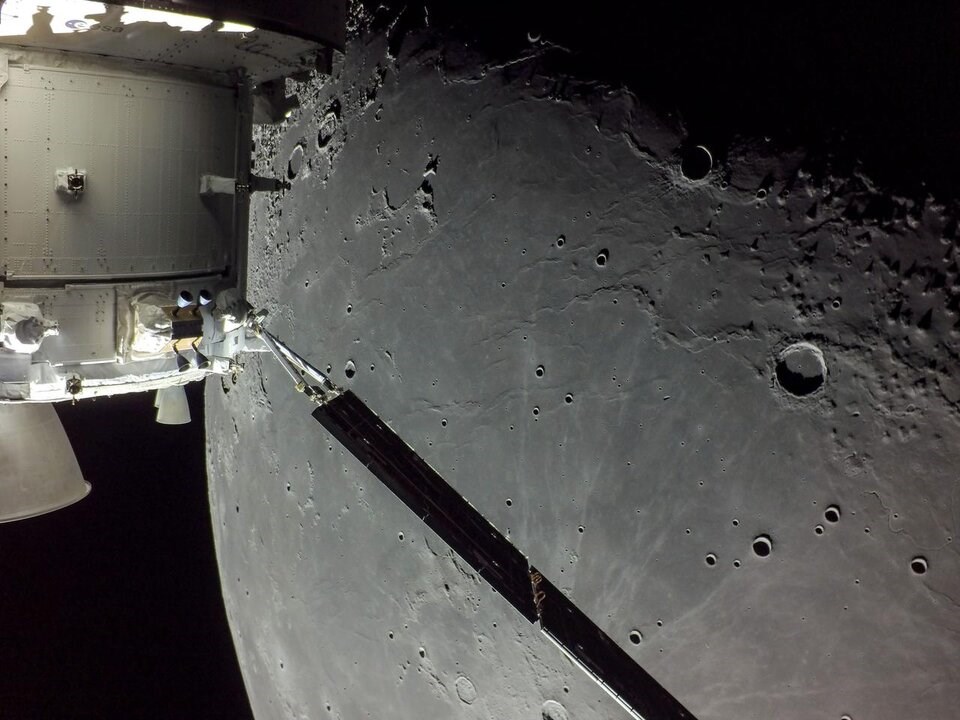

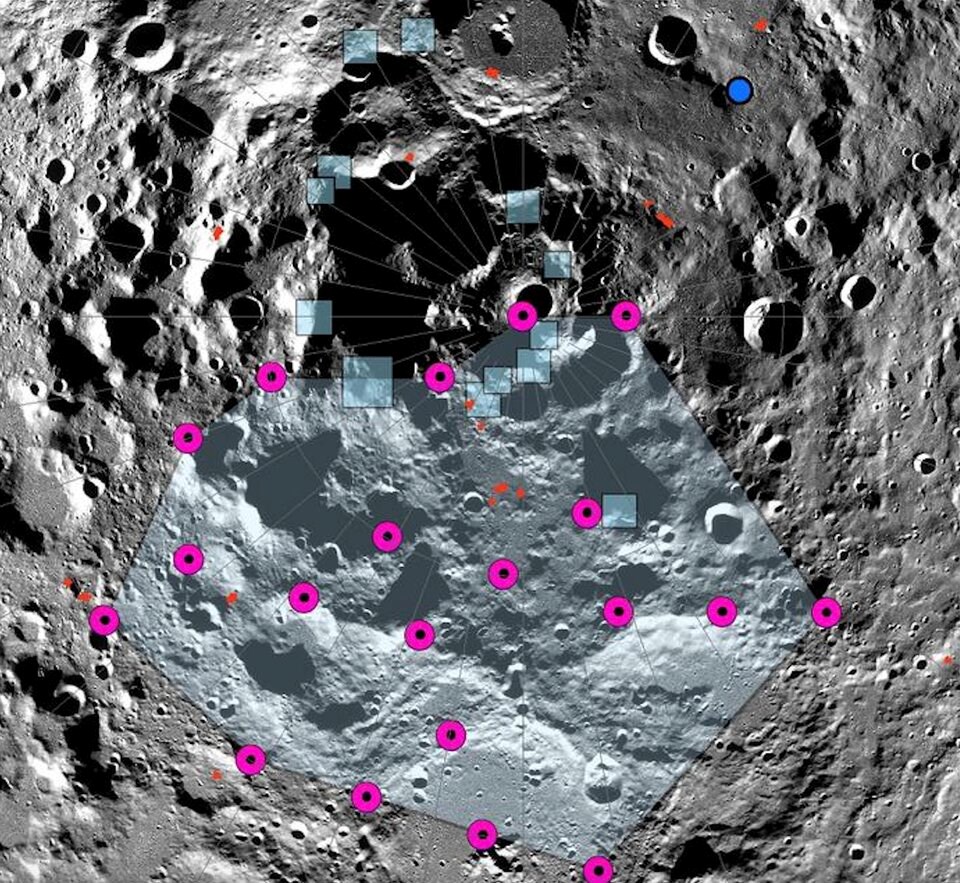

The research team used NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to pinpoint the source of seismic activity to the moon’s south pole.

Many of the small thrust faults captured by the researchers are “likely still active today,” the study found. But unlike the quick duration of terrestrial earthquakes, some of those recorded on the moon can last hours at a time.

One of the events analyzed in the study was a magnitude 5 moonquake recorded by the Apollo Passive Seismic Network in the 1970s that lasted an entire afternoon and was one of the largest ever recorded.

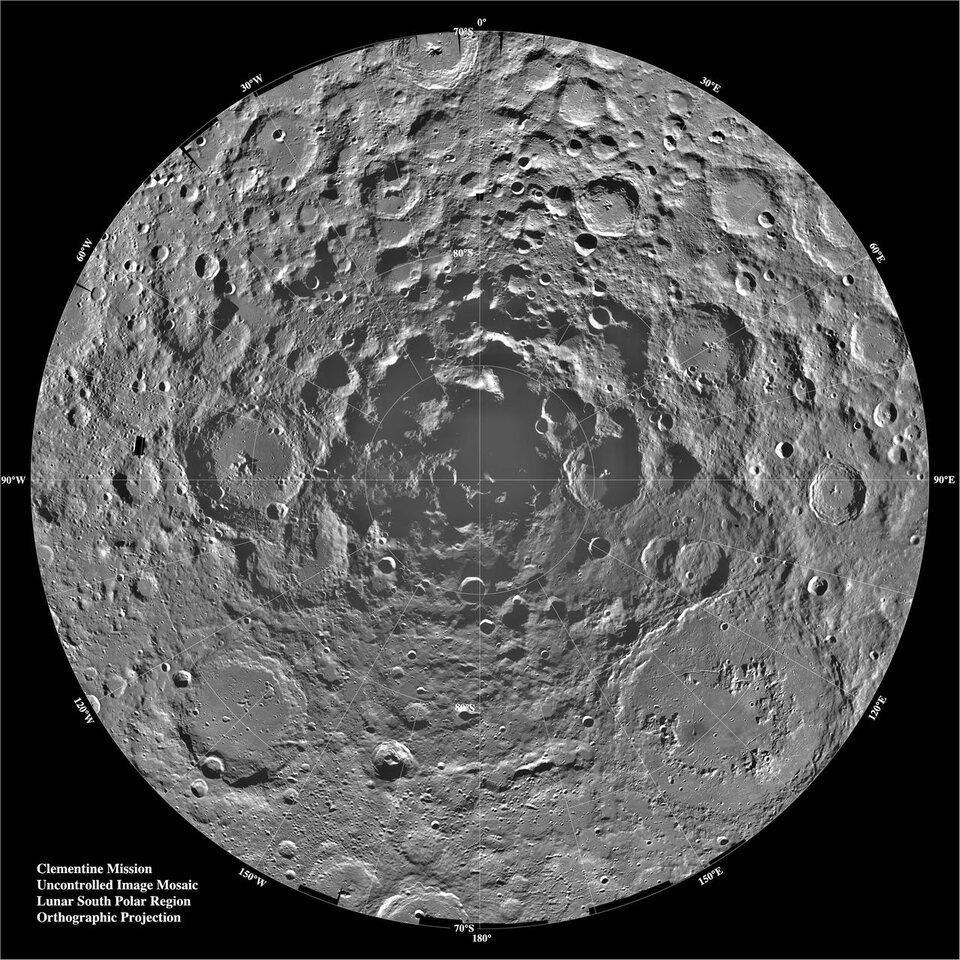

Based on their analysis, the researchers concluded that seismic activity on the south pole could pose “a potential hazard to future robotic and human exploration in the region.”

Osinski, who didn’t take part in the research but has helped train Canadian astronauts for upcoming missions, says the findings suggest engineers will have to take the seismic activity into account in the same way people design structures in earthquake-prone regions on Earth.

“Given none of the previous missions to the moon have been affected by moonquakes, I think the upcoming robotic and human missions are hopefully safe,” he said. “We would have to be incredibly unlucky to have a moonquake during one of these missions.”

A new era of moonshot missions heats up

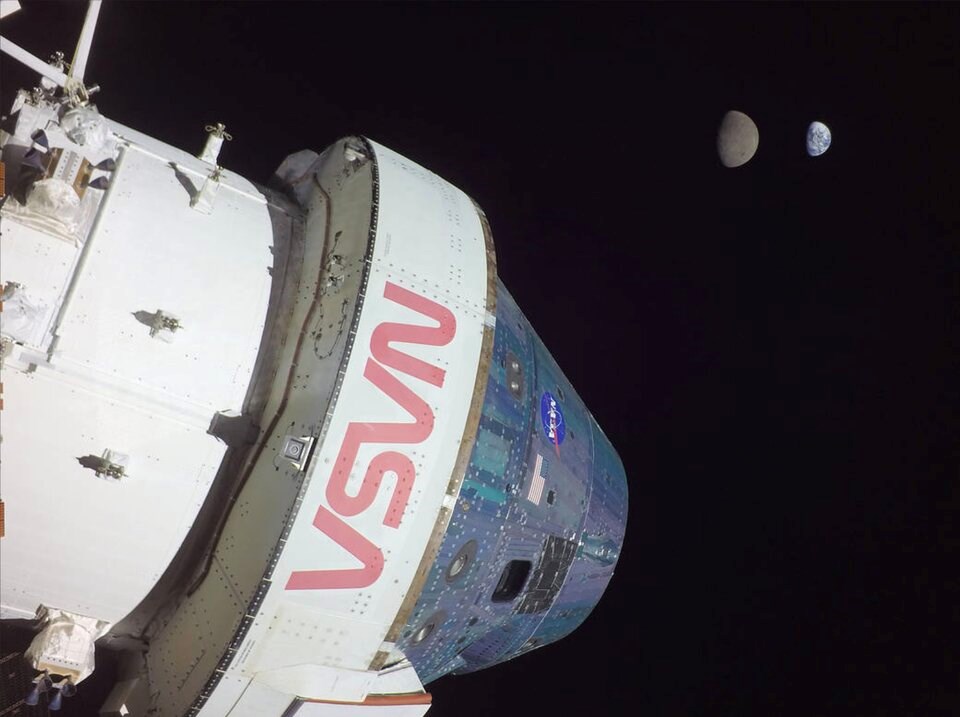

On Dec. 11, 2022, Artemis 1 touched down in the Pacific off the coast of California, capping an un-crewed trip around the moon. The spacecraft carried a number of payloads on-board, including an experiment that seeks to develop countermeasures to protect humans against cosmic radiation.

In September 2025, Artemis II is scheduled to take four astronauts, including Canadian Jeremy Hansen, in a lunar orbit in the first human test-flight of NASA’s Orion spacecraft.

NASA’s first crewed Artemis mission is slated for 2026 with the goal of eventually establishing a long-term presence on the moon.

The landing, which is set to target the south pole, will mark the first time in more than 50 years that humans have set foot on the lunar surface. It is also expected to mark the first time a woman and person of colour will walk on the moon.

By establishing a moon base or possibly a colony, missions to the moon look to learn what is required to live and work in a lunar environment — one that faces a 300-degree-Celsius temperature swing between night and day.

Artemis IV, currently on track to launch in September 2028, is scheduled to bring two astronauts to the moon’s surface, while continuing to assemble Lunar Gateway, a deep space outpost orbiting the moon meant to act as a staging point for further exploration.

Roughly 400,000 kilometres from Earth, the station will eventually be home to Canadarm3, Canada’s largest financial contribution to the Artemis missions.

Some hope the moonshot missions will prepare for future missions to Mars. Others say human presence on the moon will allow scientists to set up radio-telescopes on the dark side of the moon. Shielded from human radio waves, such an observatory could open up an ideal outpost to monitor the universe.