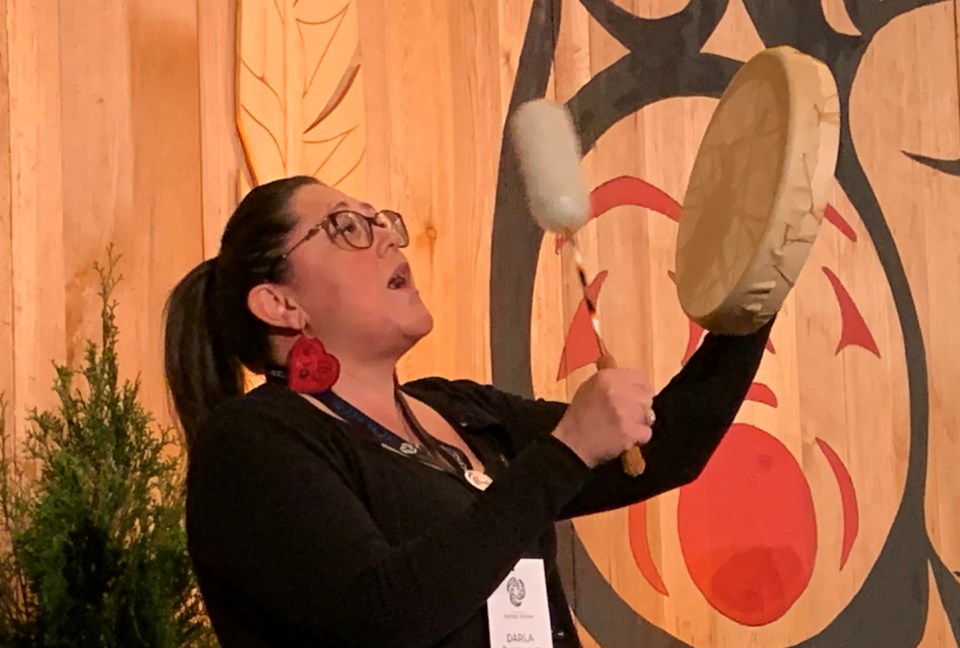

Too many of her family members have fallen through the family, health-care and justice system cracks and lost their lives, Darla Rasmussen told B.C. First Nations Justice Council (BCFNJC) April 8.

Rasmussen addressed hundreds of delegates as the council released the final draft of its Indigenous Women’s Justice Plan (IWJP), a plan she said comes after two years of hard work and listening to people around the province.

The plan centres on the safety, well-being and dignity of women, girls and LGBTQ+ and two-spirited people in a system where they have long been over-represented.

“We need to show up and be present when somebody comes into our courtroom or our office space and we need to ask, ‘Are you hungry? Are you tired? So you feel safe, can we have this conversation?’” Rasmussen said. “We need to start working form our hearts and listening to those stories to better understand and have empathy and compassion.”

“Justice doesn’t need to be rigid,” she said. “Approaches to a new way of working is going to be hard. It’s going to be challenging, it’s going to be stressful. It’s also going to create healing and connection.”

BCFNJC chair Kory Wilson told Glacier Media many of the multiple issues addressed in the draft centre around poverty. Those issues need to be addressed by governments, Indigenous court workers and restorative justice employees, she said.

“Everyone has a responsibility to help this move forward,” Wilson said.

She said Indigenous women today are still at the margins of society and at the negative end of Canada’s socio-economic indicators.

“We need to transform the justice system so that my three daughters are not likely to be incarcerated, or worse, because they are Indigenous.”

Council statistics indicate Indigenous women currently account for half of the total inmate population in Canada while accounting for only four per cent of the population.

The council said the plan’s development was guided by the principles that such people hold sacred roles in their communities as matriarchs, knowledge keepers, healers, teachers, artists and storytellers.

“The IWJP is meant to support their self-determined pathways to justice and make their solutions and demands a reality,” the council said.

However, implementation is something that requires engagement and planning, as well as funding from both the federal and provincial governments, the council said.

Council member Lydia Hwistum called the plan “a comprehensive, Indigenous-led response to the rampant violence and discrimination that is continuing to harm our Indigenous women, girls and 2S+ people.”

The report came about from recommendations from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls report, the Red Women Rising report and the Highway of Tears Symposium report.

The 48-page document pulls together a comprehensive list of objectives and goals in the areas of accountability, legal aid, Indigenous justice centres, policing, sentencing reports through the Glaude system, corrections, transportation and cellular connectivity, crisis response, child welfare, First Nations court, Crown prosecution, and LGBTQ2S+ supports.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, told conference attendees that people need to support each other to move rights forward.

“We live in the shadow of colonial fear,” he said. “We have to face the reality of taking control of our lives.”