Public health officials are encouraging parents to ensure their children get routine childhood vaccines as measles continues to spread around the world. Here are some facts about one of the most contagious but preventable diseases.

WHY IS VACCINATION BEING URGED IF CANADA DECLARED MEASLES ELIMINATED IN 1998?

Measles is making a comeback globally due to declining rates of routine childhood vaccinations, some due to missed appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, myths and misinformation that sometimes involve alternative practices are contributing to vaccine hesitancy. Travel to and from countries with low vaccination rates has led to an uptick in cases in Canada among those who are under-vaccinated or unvaccinated. But some cases have not been linked to travel, suggesting community spread.

HOW CONTAGIOUS IS MEASLES?

The Public Health Agency of Canada says that in a group of 100 people who have never had a measles infection, 95 need to be vaccinated to prevent the disease from spreading. It's possible to be infected from contaminated air up to two hours after an infected person has left a room so vaccination rates must be high to prevent outbreaks. A travel health notice for measles is currently in place for all countries. It says anyone who is not protected against measles is at risk of being infected when travelling abroad.

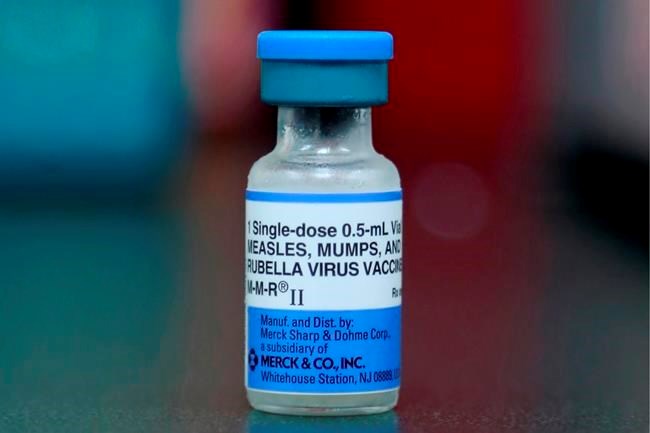

WHEN SHOULD THE MEASLES VACCINE BE GIVEN?

Children are given the initial dose around their first birthday and the second dose before or soon after they start school. It's available as the measles, mumps, rubella vaccine or the measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, for the second dose. While the efficacy of a single dose is estimated to be 85 to 95 per cent, it's almost 100 per cent with the second dose.

Infants as young as six months can be vaccinated if they are travelling to regions where measles is a concern. The Public Health Agency of Canada says in that case, the routine two-dose series must be restarted on or after the child's first birthday so that a total of three doses is given.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS AND COMPLICATIONS OF MEASLES?

Initial symptoms such as a fever, cough and runny nose can be similar to a cold or flu. However, some distinct features include small, white spots inside the mouth and throat as well as red, watery eyes. A red rash develops on the face and spreads down the body.

Severe complications include pneumonia and encephalitis, or swelling of the brain. Pregnant people could experience miscarriage, premature labour and have infants with low birth weight.

SHOULD ADULTS GET VACCINATED?

The Public Health Agency of Canada has said people who are unsure if they've received two doses of the vaccine should talk to a health-care provider about getting a booster shot — especially before travelling.

People born in 1970 or later should ensure that they have received two doses. Those born before 1970 are generally assumed to have acquired immunity to measles from an infection. They should ensure they have received one dose of the vaccine before travelling.

Officials and health experts have said there is no harm in getting another dose of the MMR vaccine, even if it turns out that an individual was previously vaccinated.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 15, 2024.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

The Canadian Press

Note to readers: This is a corrected story. A previous version erroneously referred to varicella as smallpox instead of chickenpox.