Next time you arrive home with aching, blistered feet after a long day, take heart: It’s not your feet that are the problem. It’s your shoes.

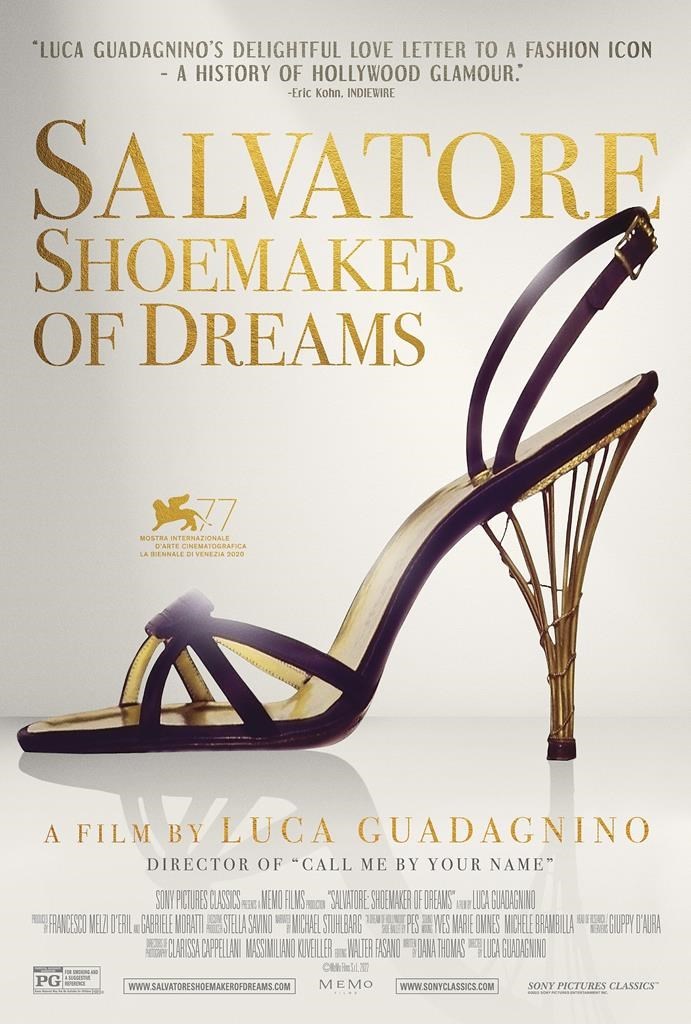

And that comes from the master, the late Salvatore Ferragamo, who pronounces in director Luca Guadagnino’s loving documentary “Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” that in his entire career, “I have found there are no bad feet. There are bad shoes.”

Now, whether you can afford a pair of Ferragamos to let your feet live their best lives is another question. But it’s fascinating to learn how obsessively Ferragamo, born into a poor Italian farming family at the turn of the 20th century, studied the human foot in his quest to create the perfect shoe, combining creativity with, crucially, comfort. “I love feet,” he wrote. “They talk to me.” He even studied anatomy as a night student at the University of Southern California, peppering the professor with questions about the skeleton — but only the feet.

That's just one of countless lovely anecdotes packed into Guadagnino's often fascinating, unabashedly adoring and also perhaps somewhat overly stuffed study of the designer, using Ferragamo’s own voice from recordings, and his 1955 memoir narrated by actor Michael Stuhlbarg. Working with the Ferragamo family, the director had an astonishing wealth of material to choose from: Between the family foundation and museum archives, numerous family members to interview, a slew of top cultural commentators and also some wonderful old Hollywood footage, you can almost feel Guadagnino efforting to get it all in. Then again, he knows some of us could watch films about Hollywood, about fashion, and especially about great shoes all day long.

And these ARE great shoes, especially if you like shoes that tell a story. For example, the famous “rainbow” shoe produced in the late ’30s, a glistening gold sandal perched atop a platform of layered suede tiers on a sole made of cork — a welcome innovation at a time when leather could be hard to come by (Ferragamo pioneered platform soles and the wedge heel). Shoe lovers will enjoy a segment where we watch this shoe being constructed today, looking stunningly contemporary, step by step: the cutting, the gluing, the hammering. (The shoe later stars in its own mini-film, a whimsical animated “shoe ballet” closing the documentary.)

Then there's the almost dangerously, rebelliously sexy shoe worn by Gloria Swanson in the 1928 “Sadie Thompson,” a pair of high-heeled black pumps with an ankle strap and large white bows that scream out: “Look at me!”

We begin, though, with Ferragamo’s youth as the 11th of 14 children, in Bonito, a village near Naples. Pushing back against his father's views that shoemaking is a lowly career, he proves his worth by producing overnight a pair of spiffy shoes for his sister's confirmation. He apprentices with a cobbler at age nine, is making shoes by 11, and at 16 boards a ship to America. After a quick stop in Boston he hops a train and heads west — to Santa Barbara, California, where a fledgling movie industry is emerging. As director Martin Scorsese says — the best of many commentators here — in California, “anything goes. You could make yourself over three or four times.”

Watching early Westerns, Ferragamo knows he could make better cowboy boots — and he does. Then he graduates to all sorts of movie shoes, including 12,000 sandals for Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 silent epic “The Ten Commandments.” His name grows and his fans include the biggest stars of the day — Swanson, Mary Pickford, Lillian Gish, Douglas Fairbanks (and in later years, everyone from Greta Garbo to Audrey Hepburn to Marilyn Monroe.) He relocates to Hollywood, where he lives near Charlie Chaplin and Valentino stops by to chat in Italian. He establishes his own store, a magnet for stars.

Guadagnino gives us a lesson in the history of Hollywood itself, not to mention the birth of the “movie star" and the role fashion has played in that. (It’s great fun.) Then in 1927 Ferragamo returns to Italy, choosing Florence as a base for his plan to use Italian artisanal labor to make shoes destined for clients in America. It's a plan fraught with risk and early setbacks. In 1933 he declares bankruptcy, then rebuilds and eventually buys a lavish 13th-century palazzo for his company — a triumph of self-belief.

Despite seemingly countless interviews with family, there's still a feeling we’re not always delving deeply into the man’s character or personal life. That finally changes when, late in the film, through lovely footage shot by Ferragamo himself, we meet his bride, Wanda, a young woman from his village.

It is Wanda who will, at 38 and a mother of six, take over the business when her husband dies suddenly of illness in 1960, overseeing an expansion into a global luxury brand. But that is not covered here. Wanda Ferragamo died in 2018, at age 96 (luckily she'd been interviewed for the film), and her years atop a business empire after never having worked in her life would have been a fascinating element of this story.

But that will have to be another movie.

“Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” has been rated PG by the Motion Picture Association of America “for smoking and a suggestive reference.” Running time: 120 minutes. Two and a half stars out of four.

MPAA definition of PG: Parental guidance suggested.

Jocelyn Noveck, The Associated Press