The Polygon Gallery, the JCC Jewish Book Festival and the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre present Photography as Storytelling: a conversation with Terry Kurgan, Polygon Gallery, Sunday, Feb. 9 at 4 p.m.

The young man fled the city two days before the Nazis arrived – his thoughts mired in fear, guilt, and his flowers.

“I hope Mrs. Kara remembers to water my plants. The violets on the balcony are just about to flower,” Jasek Kallir writes in his diary entry from September 1, 1939.

Kallir left Bielsko, Poland and journeyed from Romania to Turkey to India and to South Africa, where he raised a daughter. His daughter would stay in South Africa to raise her own child, a daughter named Terry Kurgan who would grow up to be an artist and photographer.

Kurgan was 15 when Kallir died. “Too young to be curious” about her grandfather, she reflects.

But in recent years Kurgan found herself wondering about who her grandfather was and about his escape.

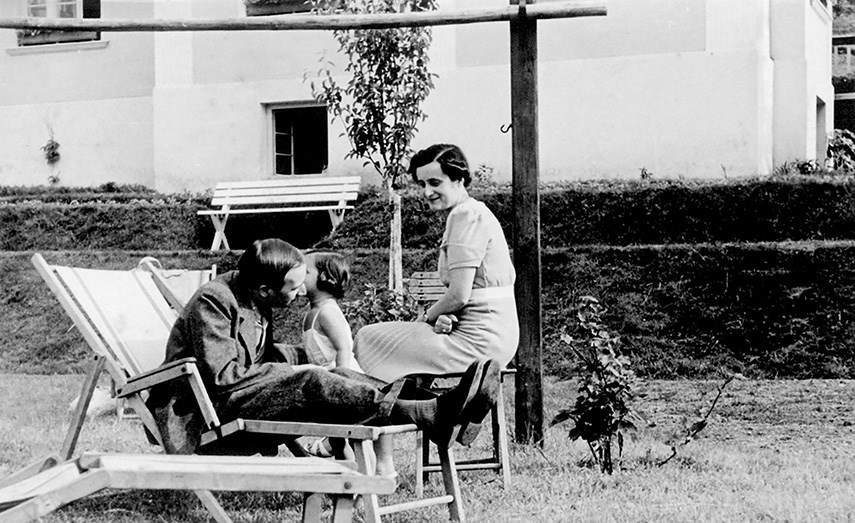

She’d seen his photos but now she studied them. Her mother had his diary. Kurgan had it translated and found 20 years of writings, records of her grandfather’s dreams, notes on his family and efforts at psychoanalysis.

“I have an enormous amount in common with him,” she reflects, speaking to the North Shore News from a restaurant in Johannesburg.

Her grandfather, she realized, was an introspective intellectual with an abiding appreciation for art. But for Kallir, South Africa was an alien culture.

“I began to understand how much he must have been living the wrong life,” she says.

She delves into that life in Everyone Is Present, a “hybrid, cross-genre book,” that represents the culmination of nearly 40 years of fine art practise. It may also be the result of a single question.

“Well, what’s next?” Kurgan’s publisher asked her.

Kurgan explained her nascent idea to combine photos and diary entries. Intrigued, her publisher encouraged Kurgan to pen a series of essays.

The result is a memoir-travelogue-creative non-fiction book that Kurgan says had been percolating in her unconscious for years.

She followed a “detective trail,” tracing her grandfather’s life and augmenting his diary with historical records.

Days after her grandfather fled his city, Nazis burned the Bielsko Synagogue and forced rabbis to throw sacred texts into the fire. To deepen her understanding of what the city had been like, Kurgan delved into the memoir of Gerda Weissmann Klein, a Polish-American writer who lived a few blocks from her grandfather. Klein described Nazis marching in the streets and a neighbour who handed roses to a German officer.

Kurgan also found a YouTube video that featured photos of the occupation, including a picture of an SS officer holding white roses.

That combination of words and images was a “precise and visceral encounter with the past,” Kurgan writes. “What are the chances of an observation my grandfather makes and records in his diary in 1939, aligning with an incident described in a memoir first published in 1957, and all of that actually existing in a photograph . . . uploaded onto YouTube in 2014.”

There are haunting passages in Everyone Is Present. Kallir recalls riding next to a rabbi and his family in the back of an open truck driven by a farmer.

“He took us only as far as Auschwitz where we changed to a train,” Kallir writes.

In the late spring of 1939, Auschwitz is “still simply just a word,” Kurgan explains, noting the horrors that would follow.

The book is divided into three sections: home and origins, a journey, and a return.

“Writing this book was really trying to make sense of what I’d inherited. ... There’s an enormous amount of intergenerational transmission,” she says. “I think that’s what drove the project, what my mother, his daughter, delivered into my unconscious,” she concludes before adding: “Not to sound too much like psychobabble.”

Besides chronicling Kallir’s escape, the book is about what he escaped to.

He arrives in South Africa, “just as white voters give a majority in the Union parliament to an Afrikaner nationalist party that owes aspects of its rhetoric to national-socialist ideology,” notes Queen Mary University of London professor Andrew van der Vlies in his review for the blog Africa in Words.

The book is a piece of history but Kurgan believes many people will relate to her grandfather’s journey.

“The global refugee story is a story here too,” she says.

Perhaps the most painful section of the book is Kallir’s diary entry from Sept. 1, 1939.

“I fear I am abandoning my post too early,” he writes, “but console myself with the thought that I believe in Poland and will be back soon.”