Sue Hall’s son was given a great gift, but, like a pair of grey socks gifted at a child’s birthday party, for ages it had been something he’d rather have left unopened.

Hall’s son was a picture learner. His way of thinking was three dimensional, shape-shifting and physical in nature.

However, when it came to the 2D-world, such as letters and words on a page, things were more of a challenge. He couldn’t envision what was in front of him in the same sophisticated way he could if it was a 3D problem-solving exercise, for example, explains Hall.

“The gift of dyslexia is that we have the natural ability to alter perception,” she says. “We have a 3D way of thinking. But if you take it to the 2D-world, it’s more problematic.”

It’s not problematic because people living with dyslexia have an incorrect way of looking at things, she says, adding that it’s a problem with the system itself – a society or education system that doesn’t necessarily cater to the dyslexic learner’s unique take on reality and learning.

“They’re totally capable of learning, they’re just little Apple Macs in a PC system,” says Hall.

Hall’s son was 10 years old when the dyslexia he’d lived with his whole life became more manageable, shortly after Hall became a Davis Dyslexia Correction facilitator and was able to offer more help for her son.

Dyslexia is neurobiological in nature and, simply put, can be defined as an unexpected difficulty in learning to read.

She notes with pride that her son, now 33, is in the process of completing his PhD.

And it’s because of this that Hall, who has now spent decades as a facilitator helping kids living with dyslexia achieve their full potential, says she’s fed up with the often negative image associated with people living with it.

“It’s only talked about in the old definition. The old definition is that there’s something wrong with our brains,” she says. “I’m old enough now to be getting very tired of children arriving at my doorstop telling me they’re stupid when they’re not.”

In 2001 Hall founded the Whole Dyslexic Society, a North Vancouver-based organization that aims to improve awareness and clarity of what dyslexia is as well as provide bursaries for certain programs devised to help dyslexic learners.

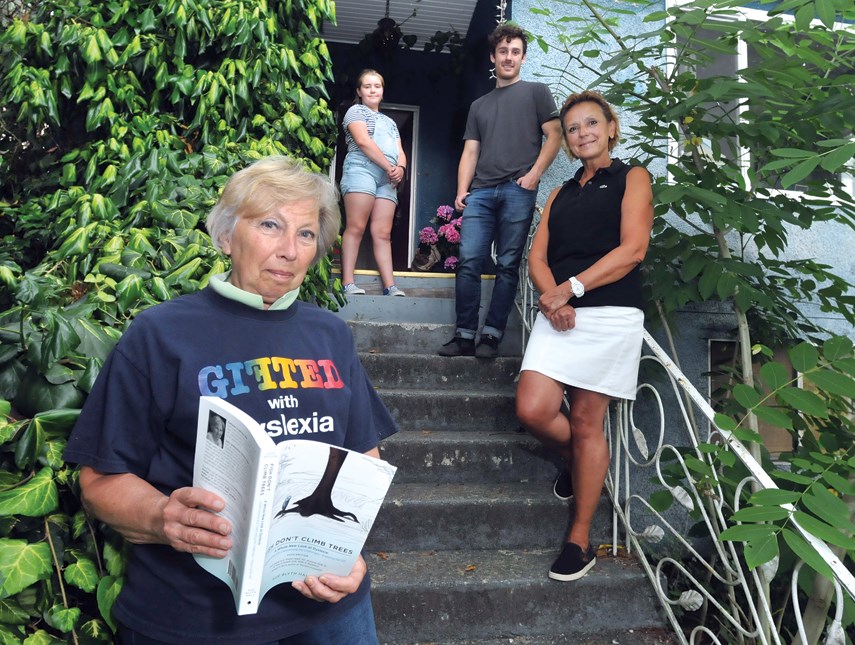

Hall has also published a book called Fish Don’t Climb Trees, which recounts her and her son’s journey with dyslexia, as well as touches on the stories of some of the clients that Hall has helped along the way.

“They simply have a different way of learning and if we show them how to control their gift, which is a perception ability, and if we show them how to learn to read the way they were born to read, then they’re not going to struggle in school,” she says.

For the month of August, the Whole Dyslexic Society is hosting a virtual fundraiser called Walk and Talk the DYS out of Dyslexia.

The goal of the fundraiser is to have participants walk a cumulative 8,000 kilometres in their own backyards. Participants are asked to get sponsors or donors who will give money for every kilometre walked.

“I’m trying to do five-km a day for one month,” notes Hall.

Monies raised during the one-month event will go towards the Whole Dyslexic Society’s bursary fund, says Hall.

“Particularly with COVID, when you’re having people that might not be as well off as they might have been even last year, we need to make sure the bursary fund has the money in it,” she says.

Visit thewds.org/pagewalkandtalk for information on the fundraiser.