The artist would wear about five layers of grubby clothes while the models wore nothing at all.

Armed with pad and pastels, Stephen A. Corcoran carefully sketched the models – it didn’t matter who it was, male or female, tall or short, lean or stocky – in a multitude of poses.

Drawing and painting was good for Corcoran. The lines he created were vivid and imaginative, full of colour and light and always managing to capture something of that allusive quality that artists are so capable of bringing out.

For Corcoran, who friends and family called “Steve,” several years of artistic practice left an impression. He had more confidence, more structure in his life, and he became more adept at transferring the thoughts in his head onto the paper or page or canvas right in front of him.

As someone who lived with schizophrenia for decades, Corcoran had a unique, and at times what appeared to be a disordered, perception of reality. Art helped that perception of reality come into focus.

“There’s nothing more real than a naked person,” says Joan Boxall, Corcoran’s younger sister, of the artistic practice her brother worked so hard at during the last decade of his life. “He was anchoring down every week for three hours into reality.”

Mind games

Steve Corcoran passed away in 2013, just a couple weeks shy of his 65th birthday.

“I like to think he was such a hippie that he wasn’t ever to become a senior,” muses Boxall, who has lived in North Vancouver for the past 25 years.

Boxall and Corcoran grew up in the Kerrisdale neighbourhood of Vancouver, two of seven siblings in a bustling Catholic family. Like all relationships, theirs ebbed and flowed. Boxall was five years younger than her older brother and by the time she was just coming of age, he had already left the house.

Describing the brother she grew up with as a “die-hard hippie” with a “very artistic temperament,” Boxall says her and Corcoran’s age gulf meant they weren’t particularly close when they were young.

“I’d had a decade to get to know him in effect, but it wasn’t to be then,” she says.

When Corcoran left home, it was with a dreamer’s sensibility. He worked at a mill, trained as a welder, lived communally, got married and had sons, worked as a tree planter and mushroom picker, and attempted to study at the former Vancouver School of Art.

Along the way, his artistic quest was stalled and his mental health deteriorated.

While in his 20s, Corcoran’s behaviour might have been described as erratic, but in actuality he was at the beginning stages of a mental health battle that would last the rest of his life.

“He would show up to family gatherings, Sunday dinners and things like that, but he would always be talking about things that were kind of strange – interrupting and going off on tangents,” says Boxall. “He would have been exhibiting, but everything got muddied, I think, by him being kind of bohemian.”

As brother and sister came and went and for the most part lived their separate lives for the better part of a decade, things got worse for Corcoran. After not seeing her brother for several years, Boxall bumped into him at a Kitsilano grocery store one day.

In the throes of his recently diagnosed mental health challenge, Corcoran appeared “so thin and gaunt and ranting,” according to Boxall.

Boxall was 30 years old the year she ran into her brother at that Kits grocery store. She had recently got married and was relishing a rewarding career as an English teacher. The brother and sister continued to drift apart during the ensuing years and decades, always finding themselves in such wildly different stages of life.

“It wasn’t until after my parents passed away and I was 50 that I came on board,” says Boxall. “Steve was quite isolated by then. I didn’t know how isolated he was. …”

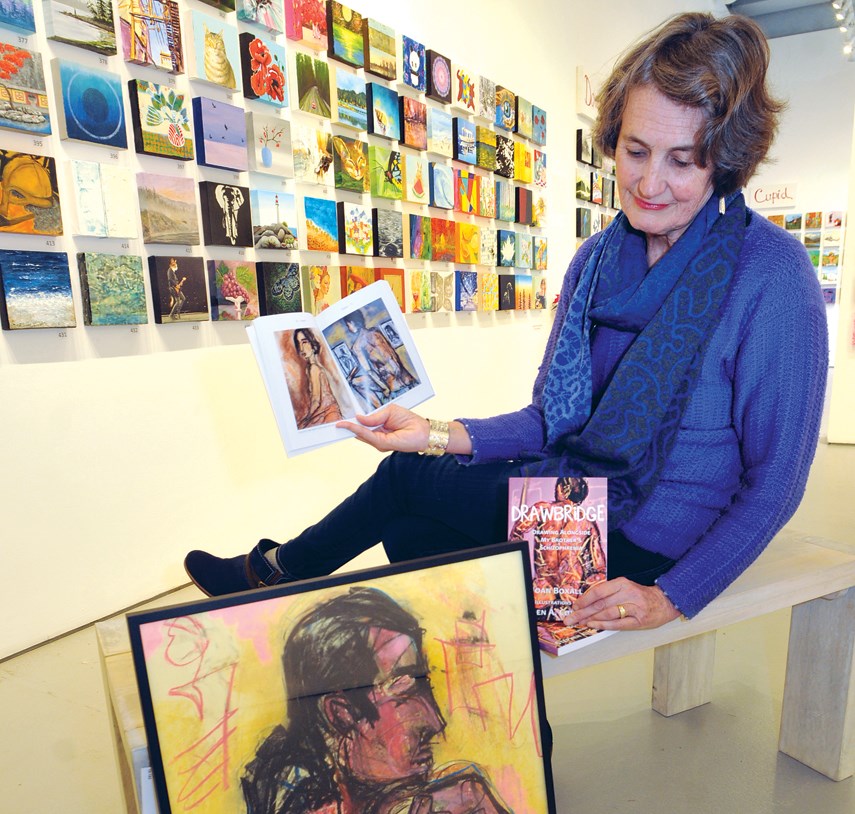

The story of how brother and sister, who grew apart due to the circumstances and complexities one often faces in life, came to finally forge a real connection is the subject of Boxall’s new book, DrawBridge: Drawing Alongside My Brother’s Schizophrenia.

A work of creative non-fiction, the book traces the 10-year period where Boxall and Corcoran were in each other’s lives every week again, creating art and finally getting to know one another, right up until Corcoran’s passing in 2013.

“I thought this story has to be told, how art helped Steve. It’s so important,” says Boxall.

Portrait of an artist

Living with schizophrenia can feel like coming apart at the seams. The disease affects how a person thinks, feels and behaves. Research suggests it can be many illnesses masquerading as one – a biochemical imbalance in the brain which can lead to a decreased ability to understand reality and bringing with it a slew of other mental health challenges.

Approximately one per cent of the population is affected by schizophrenia, according to the Schizophrenia Society of Canada.

And while there’s currently no known cure, there are good and effective treatment options available.

For Corcoran, his re-awakening to the art world aided in his recovery by giving him confidence and purpose, according to Boxall.

In the early 2000s, having reunited, Boxall and her brother started spending time together every week. In search of an activity for the pair to do together, and remembering her brother’s artistic ambitions from his youth, Boxall says the eureka moment occurred when she happened to pick up a brochure for a program run by the Vancouver Recovery Through Art Society.

That program, called the Art Studios, supports the society’s mandate to provide innovative mental health and addiction recovery and growth through art, explains Boxall.

Corcoran was nervous during his initial sessions, so Boxall accompanied him. As soon as he got there, he started a 10-week sketch class, and the spark was reignited.

“I was his advocate. When I saw that his artistic talent was still there, that his creative mind was still there, I just couldn’t do enough for him,” says Boxall. “They do tremendous good. It was the only thing that helped my brother.”

Corcoran attended the program on and off for two years, eventually completing all available sessions in drawing, painting, pottery, printmaking and mixed media.

Ann Webborn, vice chair of the Recovery Through Art Society, says someone like Steve can benefit from the confidence-building and skills-building nature of the program.

“A lot of people who have a serious mental illness have been in hospital, and they also lose a sense of their identity,” says Webborn, who also serves as an occupational therapist in the Art Studios program. “When it comes to the Art Studios, they develop a new role – which is as an artist.”

Webborn adds that last year the program received 130 new referrals, with 20 per cent of those referrals being for youth under the age of 25.

While Corcoran was far from his youthful years when he first entered the Art Studios, his exceptional output there stirred the fire within him to continue his artistic endeavours, with Boxall by his side. In the following years, Corcoran would start creating works in a life drawing group.

He would eventually go on to exhibit more than 50 of his works in solo shows, and his work is currently on display at CityScape Community Art Space in North Vancouver.

In addition, after Corcoran passed away Emily Carr University of Art and Design, the school he’d always wanted to attend, helped establish the Stephen A. Corcoran Memorial Award, which supports students living with mental illness.

“I had seen such a tremendous transformation with him. He got some joy in life,” says Boxall. “The structure helped him, and then he started to complete these drawings and slowly, as a couple of years went by, people were commenting. … He was getting something other than stigma.”

Drawing to a close

Corcoran’s artistic story runs in tandem with another creative journey. In semi-retirement, Boxall had been experimenting with creative non-fiction, as well as poetry and travel writing. Her brother passed away shortly after she’d taken the plunge and enrolled in a writing program.

After the program ended, she felt inspired but also “tired and dumbstruck.” She couldn’t write Corcoran’s story, which was also her own story, right away – it would have to wait.

“I left it for a year, and then I put together a binder … because I had taken photographs of Steven’s work through the 10 years and how he had progressed and how he had blossomed with the art,” she says.

But her book is also about how a brother and sister reconnected, or perhaps more accurately, for the first time finally, truly found a connection.

As she writes in her book: “For us, drawing was a bridge thread that spanned mental illness.” But perhaps Boxall sums it up best when she talks about the way brother and sister connected over art, and how the creation of that art spread itself outward, like a web “drawing together within artistic communities, where we became enmeshed.”

“I think those 10 years really impacted me,” she says.