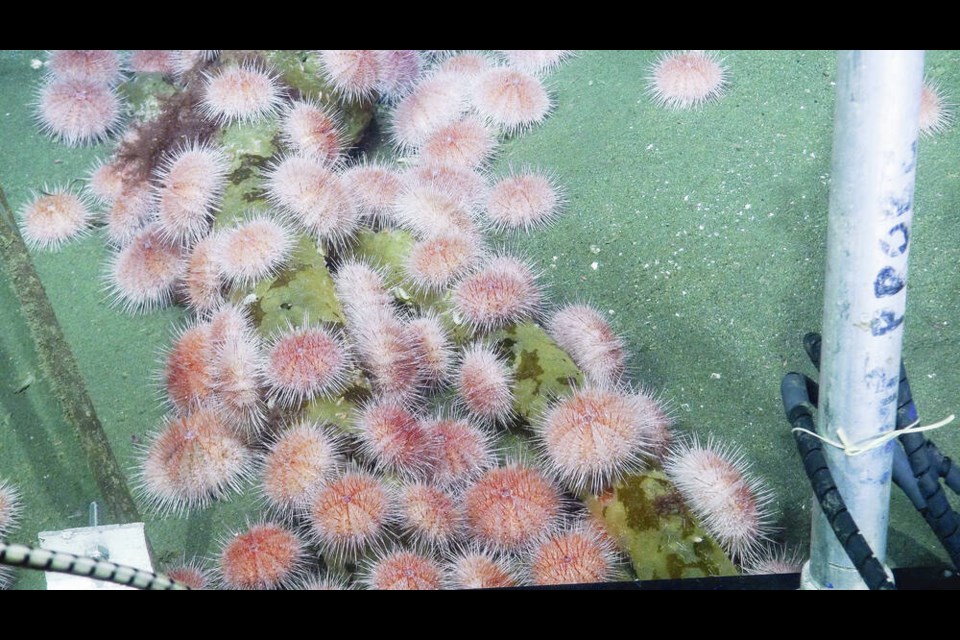

The pretty pink urchins that live in deep water off the coast of Vancouver Island have a story to tell.

They are slowly but surely moving into shallower places as food sources and oxygen levels decline due to a warming ocean.

Researchers from the University of Victoria-based Ocean Networks Canada used seven years of underwater video from the Barkley Canyon Upper Slope — part of OCN’s NEPTUNE Observatory — and other data to show the urchins are indeed on the move in search of food.

Rylan Command, lead author from Memorial University and UVic faculty of science alumni, said kelp have been slow to recover from recent heat waves along the B.C. coast, which has posed challenges for many species, including bottom-dwelling sea urchins that rely on decaying kelp for food.

The study pointed at climate-change impacts, including the so-called Blob marine heatwave that lingered in the Pacific Ocean off North America from 2013 to 2016, when surface temperatures climbed as much as three degrees above seasonal averages.

Analyzing data before, during and after the Blob, researchers found that, on average, the pink urchins moved up to 49 vertical metres into shallower water — a rate of 3.5 metres per year.

Command said warmer-than-normal surface temperatures inhibit a natural “ocean mixing” process called up-welling, where nutrient-rich water from lower depths cycles up to mix with warmer surface waters, which influences how much kelp and seaweed grow.

Another factor behind urchins relocation could be respiratory. Command said warming ocean temperatures are linked to expansion of the ocean’s oxygen-minimum zone, where dissolved O2 levels are naturally low due to poor ventilation and microbial respiration. “Marine organisms can tolerate variability in dissolved oxygen within a certain range,” he said. “But as the oxygen minimum zone expands, habitat that was previously suitable may no longer have enough oxygen for some organisms to survive.”

The Blob marine heat wave did eventually chill out. Ocean Networks Canada said 2017 started with an icy snap as B.C. experienced its first really cold weather in several years. However, longer, hotter summers have persisted since.

Four years after the Blob dissipated, video at Barkley Upper Slope showed the urchins were returning. However, in the long term, researchers expect pink urchins will continue to move into shallow water as the Northeast Pacific’s oxygen-minimum zone continues to expand, and climate change increases the frequency of marine heat waves.

The adaptation by sea urchins could have a long-lasting effect on coastal ecosystems and present economic impacts, say researchers.

Command said it could affect the numbers and distribution of shallow-water red sea urchins and green sea urchins. Red urchins are a limited-entry commercial fishery in B.C., and the recreation fishery is open coast-wide year-round. Both species are open to First Nations for food.

The study found pink sea urchins also play a key role in cycling nutrients by stirring up ocean floors and feeding on decayed organic material.

The research team analyzed imagery from 2013 to 2020 collected at Barkley Canyon Upper Slope.

They also used 14 years of Fisheries and Oceans Canada trawl surveys, covering a 760-square-kilometre area in the northeast Pacific. The data from NEPTUNE’s Barkley Canyon platform, at a depth of 396 metres, included video cameras, oxygen sensors, and tools that monitor water currents and water physical properties.

Co-author and Ocean Networks Canada senior scientist Fabio De Leo said using multiple sources tells a story of how underwater species respond to ocean change over time. “It helps us better understand how individual species and entire ecosystems are responding to the effects of climate change.”

Meanwhile, the federal government is investing $46.5 million over the next five years to see what’s under Canada’s oceans and protect it.

“It’s imperative that Canada better understand our oceans in terms of how they’re changing, how we can support their ecosystems and how we can sustainably manage resources,” Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray told a Vancouver news conference at the International Marine Protected Areas Congress Monday.

She said the research will “solidify Canada’s reputation as an ocean leader recognized around the world for [its] commitment to science, collaboration, technology and environmental sustainability.”

The funding will come from the government’s $3.5-billion Ocean Protection Plan.

Kate Moran, CEO of Ocean Networks Canada, said the $46.5 million will be used to gather data about the deep ocean for scientific research and government decision-making and to support Canada’s ocean industries.

Ocean Networks Canada will study currents, marine safety and incident response, ocean sound information to mitigate the harm of human noise on marine life and ocean monitoring for coastal communities, Moran said.

— With files from The Canadian Press

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]