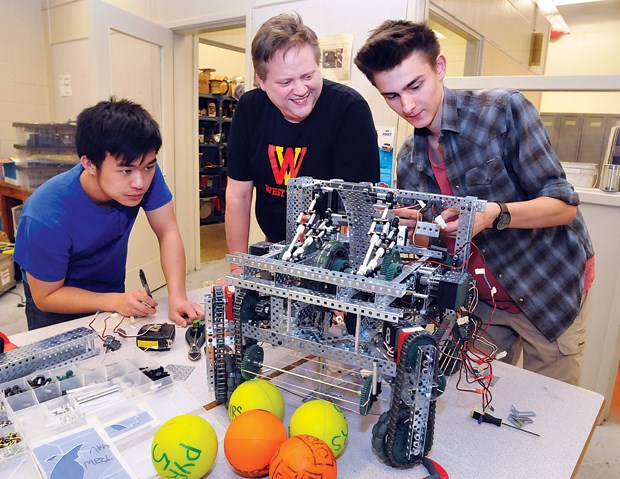

In a downstairs room at the back of West Vancouver secondary, two groups of teens are bent over a collection of wires, gears and sensors, built into what look like parts from a Meccano set.

“Can you rubber band it?” calls over teacher Todd Ablett, as Joshua White and Jesse Diaz, members of the after-school robotics club puzzle over how to attach the next part of the ‘bot.

On the table in front of them are containers with screws, steel bushings and gears, extension wires and motor controls that they’ll use to put together their ball-shooting robot for their upcoming robotics competition.

Diaz, in Grade 11, said he’s tinkered with electronics before but “this is the first year I’ve tried competitive robotics. I like to have ideas and turn them into real physical objects.”

Ablett, a teacher who has recently come to West Vancouver after years of building a successful robotics program in the Vancouver School District, recalls how he started getting interested in similar topics as a kid. “I was the first kid on my street to have any Lego,” he said. “I think that was the start of a mindset where I just wanted to put things together and figure out how they work.”

Both White and Diaz say they’re considering studying engineering when they graduate from high school.

The robotics club – which can easily run past 6 p.m. most nights – is a place where kids can experiment with turning their ideas into working machines – building, tearing them apart when they don’t work and trying a different approach.

About 15 kids – both boys and girls – are regulars in the after-school robotics club.

Next year, those who choose will be able to take their interest a step further, by incorporating robotics into their school program, as robotics and three other programs – dance, field hockey and rugby – become the latest offerings in popular specialty “academies” in the West Vancouver School District.

West Vancouver – one of the pioneers in offering specialty programs – now offers 10 different fee-paying “academies” for students attending any of its three high schools, including programs in hockey, soccer, baseball, basketball, rugby, field hockey, tennis, fencing, dance and mechatronic robotics.

North Vancouver School District also offers academies – in hockey, basketball, dance, field hockey, soccer and volleyball – as well as in digital media and the Artists For Kids studio.

The academies combine regular academic courses in the morning with intensive high-calibre training in their specialty area in the afternoon.

The West Vancouver hockey program, run out of Hollyburn Country Club, was the first academy to get off the ground in 2003.

Diane Nelson, a former owner of a professional women’s hockey team who is now director of instruction, learning and innovation, found the idea got an enthusiastic reception from the West Vancouver School District when she proposed it. Today, hockey academies are still hugely popular programs in both school districts.

Thirteen-year-old Windsor student Andrew Martin is among 70 students enrolled in North Vancouver’s hockey academy this year. Martin has been playing hockey since he first stood on skates at North Vancouver’s Karen Magnussen arena and has played defence with teams in the North Vancouver Minor Hockey Association for seven years. Martin said he signed up for the academy because he wanted to get more ice time to work on his skills in areas like slap shots, skating backwards, power plays and carrying the puck. So far, he says, it’s working.

Most of the academies in both school districts are focused on team sports. But there are also other offerings, like Argyle’s digital media academy – where students learn about animation including instruction from pros at companies like Electronic Arts – the new robotics academy at West Vancouver secondary, plus dance and arts programs.

Offering students an opportunity to excel in areas they are passionate about fits in with an increasing emphasis in schools on individual learning, says Arlene Martin, district principal who oversees the academy programs for the North Vancouver School District.

The two school districts have slightly different rules for their academies.

Students registered in other school districts and in private schools can sign up for academies in North Vancouver, although they don’t make up a huge number of students – about 40 overall. In West Vancouver, students must be registered in one of the local high schools, although occasional exceptions are made for some private school students.

Many of the students who enter the academies have already trained in their area – sometimes on high-performance sports teams – outside of school. The academies offer those students a chance to boost their skills with high-level coaches, and in some cases prepare to win spots on national teams.

Two West Vancouver hockey academy graduates – Griffin Reinhart and Morgan Rielly – were selected fourth and fifth overall in the 2012 National Hockey League draft (by New York Islanders and Toronto Maple Leafs, respectively). Rielly is now a mainstay on the blueline for the Leafs while Reinhart was traded to the Edmonton Oilers last summer and was recalled by the club on Friday after spending some time in the minors.

Colton Sissons, a graduate of the North Vancouver hockey academy, has played games for the Nashville Predators.

And two graduates of North Vancouver’s volleyball academy – Shae Harris and Sarah Chase – are now members of the national senior women’s B team while also playing NCAA volleyball on full scholarships.

Not all kids who sign up for the academies are destined to make national teams or go on to elite levels in the field. “You might not be an Olympic athlete but you might be a coach, or a referee,” said Nelson. They also learn skills like leadership and working in a team that will help them in other career paths.

There are tryouts for some sports academies– like soccer, basketball and hockey – so kids can be grouped according to their skill levels. Several academies have separate streams for elite-level athletes.

Students registered in academies are expected to keep their marks up. But there are also less tangible requirements. “For me the biggest piece is the social responsibility,” said Nelson.

More than 200 students are enrolled in West Vancouver academies. In the North Vancouver School District, that numbers is up above 500 – and growing. “I had a call from Germany this week from a student who is interested in being in our international program and interested in being part of our basketball academy,” said Arlene Martin.

At a recent open house for academies in North Vancouver, about 800 people showed up – including families with kids still in grades 4 and 5 and parents from other school districts. “They’re all interested in finding ways to challenge their children,” said Martin.

For most of the athletic academies, the school districts partner with organizations experienced in offering students high-level training in their sport. Other programs – like West Vancouver’s new robotics program – have been developed locally.

The fencing academy in West Vancouver, taught by Canadian national champion and World Cup medallist Igor Gantsevich, is the only one of its kind in Canada.

One student was so passionate about the sport he moved from Alberta to West Vancouver to participate in the academy.

“The sport attracts very unique kids,” said Gantsevich – often including high academic achievers. One student who was in the program last year was a nationally ranked chess player – perhaps not surprising as fencing involves “a huge mental component,” said Gantsevich, “in terms of mental preparation and dealing with pressure.”

In the Eagle Harbour Montessori School gym this week, about 14 students were learning that calm concentration as they tried to score points on their opponents.

There was the clack, clack of metal on metal as fencers parried, half crouching, their feet shuffling forward, their épées (swords) seeking an opening. Students wore white Kevlar fencing jackets and large metal fencing masks for protection. Thin wires ran from the tip of their épées to a lead attached to an electronic scoring system. There was a sudden run, a lunge and the scoring system beeped.

Emi Kelly, a Grade 12 student at Rockridge, said fencing teaches how to move fast on your feet – both literally and metaphorically.

Fencers also know they can’t use the same strategies with different opponents – learning how to adapt quickly is another skill.

Hunter Moricz, a 16-year-old Sentinel student, started fencing with a North Vancouver recreation program when he was nine. This year, he was one of the top eight fencers in the world at a recent European world circuit event and has qualified for the national team for the third year in a row. He’ll represent Canada at the upcoming Pan American championships and the world championships in France.

Fencing is a unique sport because of “the thinking it requires,” he said. “It’s like physical chess” – which non-coincidentally, he’s also pretty good at.

There’s no getting around the fact the academy programs come with significant costs. The programs are run on a break-even basis, but full-time programs in West Vancouver can still set families back $525 a month (or $5,250 a year). In North Vancouver, where academies run every other afternoon, the top fees are $2,500 a year. That money goes to cover costs of equipment, rental of facilities, coaching and bussing. Programs that run less often or have fewer coaching and equipment costs are slightly less expensive.

“I won’t deny these programs are expensive,” said Nelson. “We do all we can to keep the costs as low as we possibly can.”

Rob Millard, president of the West Vancouver Teachers Association, said teachers are supportive of the academies. The programs help attract students to local school districts, which translates to more funding for local schools in general, he said. In an ideal world, such programs would be publicly funded, he said. But that’s not reality.

Those lucky enough to afford it can reap serious rewards in terms of confidence and a sense of community with others who share their passion, said Nelson: “These kids are transformed.”