Radon gas is “the worst thing you’ve never heard of.”

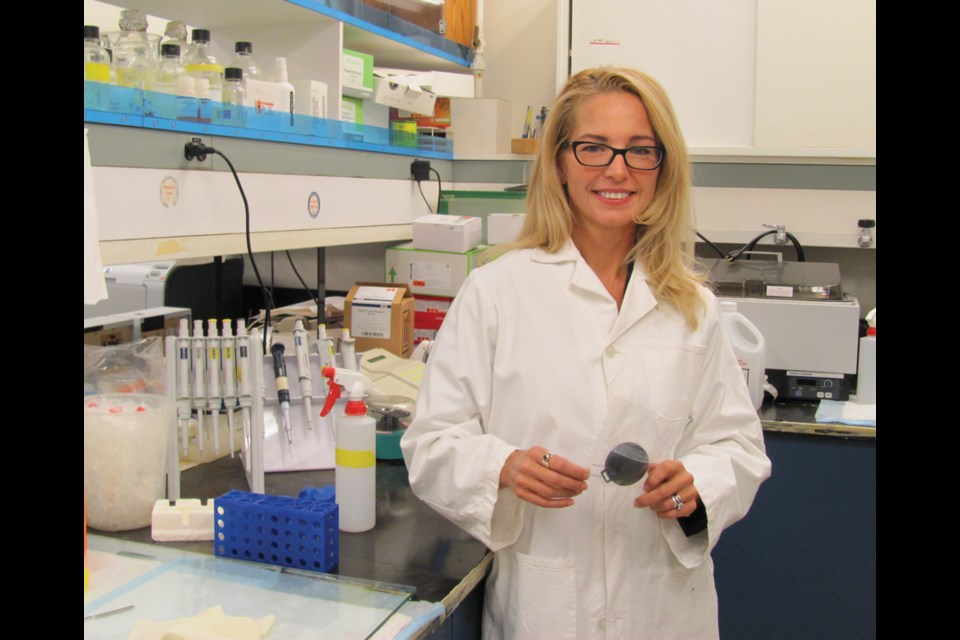

That’s according to Anne-Marie Nicol, a public health researcher who’s leading a citizen science project at Simon Fraser University to find out more about exposure to radon gas – particularly on the North Shore.

You won’t be alone if you’ve never heard of radon gas. Most people haven’t, says Nicol.

An estimated 3,200 people a year in Canada die from lung cancer caused by exposure to radon gas. But “nobody’s talking about it. How are people supposed to know?” says Nicol. “It’s not on anyone’s radar.”

Nicol and other researchers are hoping to change that, particularly on the North Shore, where some homes have tested over five times what Canada considers safe levels for radon.

Radon is created by the breakdown of uranium rock. Geologically, uranium is present in many areas of Canada, including the coastal mountains that form the backdrop to the North Shore and the Sea-to-Sky corridor. When uranium decomposes, it forms radon, which further breaks down into radioactive particles. In natural conditions, radon is easily diluted by the environment, and isn’t cause for concern. But the gas can also leak in to homes through cracks in the foundation or through pumps in heating and ventilation systems and become concentrated and trapped there. When people breathe air with high concentrations of radon over a period of time, the radiation can damage their lungs and lead to lung cancer.

Exposure to radon is the leading cause of lung cancer in non-smokers and a significant environmental cause of cancer.

It’s also completely preventable.

So far, however, it’s been an uphill battle to get much public attention, says Nicol. “It’s not Monsanto and it’s not on Facebook. There’s nobody to blame.”

“The idea that there (could be) something (deadly) inside our house – people don’t want to talk about that.”

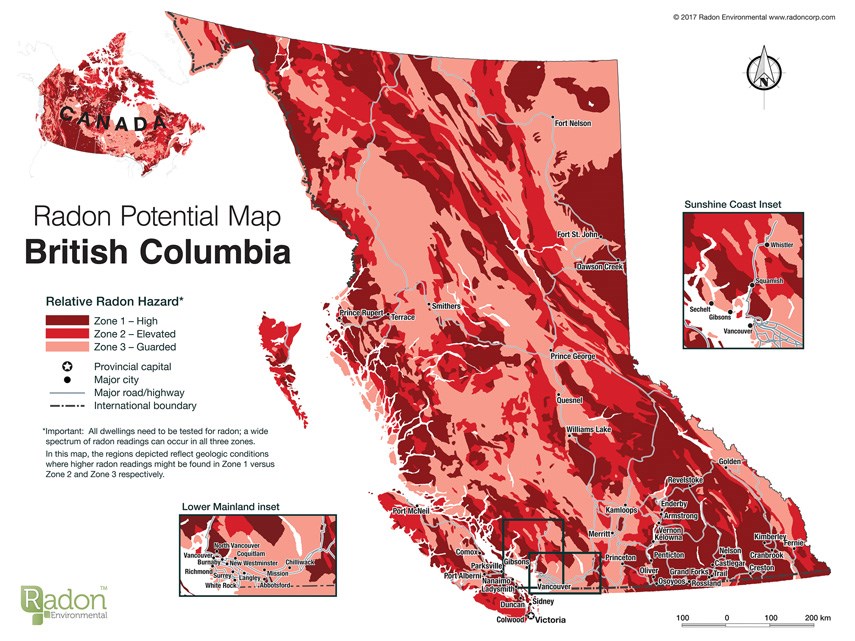

Alan Whitehead, a former West Vancouver resident, is familiar with that. Whitehead’s company, Radon Environmental Management Corp., was the first to use geological survey methods to produce maps of potential radon hazard areas across the country.

It was while his company was doing that work that his wife Janet, a lifelong non-smoker, was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Whitehead knew the area they’d moved from in Ontario was at high risk for radon potential. He contacted the people who were living in their former home and they agreed to have it tested. Within seven days he had a call from the homeowner. “She was getting extraordinarily high readings,” he said – 3,200 becquerels.

“It’s way more exposure than any radiation worker would be exposed to,” says Whitehead, noting that when they lived in the house, his wife ran a home-based business and worked long hours in a lower floor office.

While there's no safe level for radon exposure, guidelines in Canada recommend mitigation measure be put in place anytime radon levels exceed 200 becquerels per cubic metre. Levels recommended by the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States and the World Health Organization are even lower – at 150 and 100 becquerels respectively.

“It was pretty obvious Janet’s lung cancer was radon induced,” he says.

Several surgeries and seven years later, his wife is a cancer survivor.

But Whitehead remains passionate about raising public awareness about radon.

It’s a message anyone living in North and West Vancouver and in the Sea-to-Sky corridor needs to hear, he says.

While geological information merely points to the potential for radon exposure, and not everyone exposed to high radon levels will develop lung cancer, geologically speaking, areas like North Vancouver, West Vancouver, Squamish and Whistler are all high risk, says Whitehead.

“We’ve tested in most areas of the North Shore,” he says.

“Not surprisingly you’ve got lots of examples of high indoor radon levels from Whistler down through the Sea-to-Sky corridor – Squamish in particular – down to Caulfeild and Dundarave in West Vancouver.”

“We know the North Shore is particularly vulnerable in terms of its geology.”

Radon can even occur at sea level, he says. “A lot of people think because they live at sea level it won’t be an issue. But the geology is the same.”

Whitehead has seen test results of more than 1,000 becquerels of radon – five times Canada’s guideline limits – from homes in Caulfeild, Dundarave and Lynn Valley.

The only person who wasn’t surprised by the results was a woman who’d moved to West Vancouver from Florida, where radon is high and much more publicly discussed. “She’d asked the neighbours what the radon levels were and they didn’t know what she was talking about,” he says.

Her test came back at four times the recommended limits for radon.

Nicol’s project – aimed at gathering more data from potential at-risk areas – is aimed at changing public complacency.

Ten years ago, federal researchers with Health Canada did limited testing across the country and determined Metro Vancouver was at low risk of radon. But even those showed the North Shore Sea-to-Sky area at slightly higher risk than other nearby communities.

The physical characteristics of a home itself – and how it sits on the rock beneath it – can also raise or lower a risk for radon exposure.

Newer, energy-efficient homes, for instance, can trap more radon and present a bigger risk.

Nicol’s own mother, a non-smoker, died of lung cancer after working for decades as a teacher in a basement level classroom.

Children are also considered at greater risk from the DNA-damaging effects of radon on the lungs.

That’s one of the reasons Vancouver Coastal Health is also currently testing schools throughout the region for radon.

Though health officials don’t expect to find high levels, it’s worth checking out, says Medical Health Officer Mark Lysyshyn. “If you’re exposed to it over a long period of time, it could have an impact on your life.”

Fortunately, testing for radon is simple and fixing a radon problem is relatively easy and inexpensive, says Whitehead. Basically it involves putting in a venting pipe that sucks the gas from beneath the home and vents it into the atmosphere.

Many other provinces – and the Interior of B.C. – already have requirements for roughed-in radon mitigation systems built into the building code. Interior Health also now requires licenced daycares to be tested for radon.

Whitehead and Nicol would like to see all of those measures extended to the entire province – rather than just part of it.

“We’re optimistic that the B.C. government will change the building code,” says Whitehead.

“I can’t think of too many other things that we have people dying from environmental exposure that’s totally avoidable,” he says.

Nicol’s project, launched last month, involves giving out radon test kits – which look like hockey pucks. Homeowners follow instruc-tions and leave the pucks in place for three months to measure radon levels. They then receive results. Data without identifying information also goes to the research project.

Anyone can also buy their own test kit at most hardware stores, through companies like Radon Environmental or from the B.C. Lung Association for $30. Nicol says she’s happy to get results of any North Shore test if residents want to donate their data to science.

Nicol hopes to have an initial report ready in June. If she’s successful in getting further funding, she hopes to repeat the data-gathering exercise on the North Shore next fall.

The good news about radon is “it’s a very solvable, preventable problem,” says Nicol. “It’s something you can fix.”

To find out more about the project, visit www.sfu.ca/radon.html