The second in a three-part series about real estate in North and West Vancouver. Click here for part 1 and click here for part 3.

Michaela Garstin grew up in a house in North Vancouver’s Pemberton Heights that her parents inherited from her great-grandmother.

“I didn’t realize it at the time, but it was idyllic,” she said. “We would always be out in the forests and riding our bikes and running to our friends’ houses.

“It’s going to be totally different for my kids.”

Garstin, 31, has lived on and off the North Shore since those childhood days, “but I always considered North Van home,” she said.

She married her husband, a high school teacher who also grew up in North Vancouver, and started a family.

Now the couple and their 18-month-old daughter are looking to put down roots on the North Shore. But Garstin said the kind of childhood she had won’t be possible for her daughter.

“We’ll never be able to afford a house in North Van,” she said. “That’s never going to happen.”

Garstin and her husband aren’t alone. As property values rocket upwards across the North Shore, baby boomers are among the winners in the real estate gold rush. Young families are the losers.

“We call them the missing generation,” said District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton – the segment of the population between their 20s and their 40s who are quickly vanishing from the North Shore. They’re being pushed out of their communities, as even those with good jobs find they can’t afford to buy or rent housing suitable for families.

Large amounts of foreign investment means “there’s a lot of capital in the real estate market that has no connection to the local economy,” said David Eby, the NDP housing critic, who has been outspoken on the issue. “The wages that you earn in Vancouver now have little or no connection to the price of a place to live.”

For local politicians, it’s a troubling trend.

“I guess I can say my house has gone up in value and that’s great,” said West Vancouver Mayor Michael Smith. “But if my friends and my kids can’t afford to live in my community and the police officers and firefighters and the teachers and municipal workers and the workers at all the other businesses in West Van can’t afford to live here, how is that helping my community?”

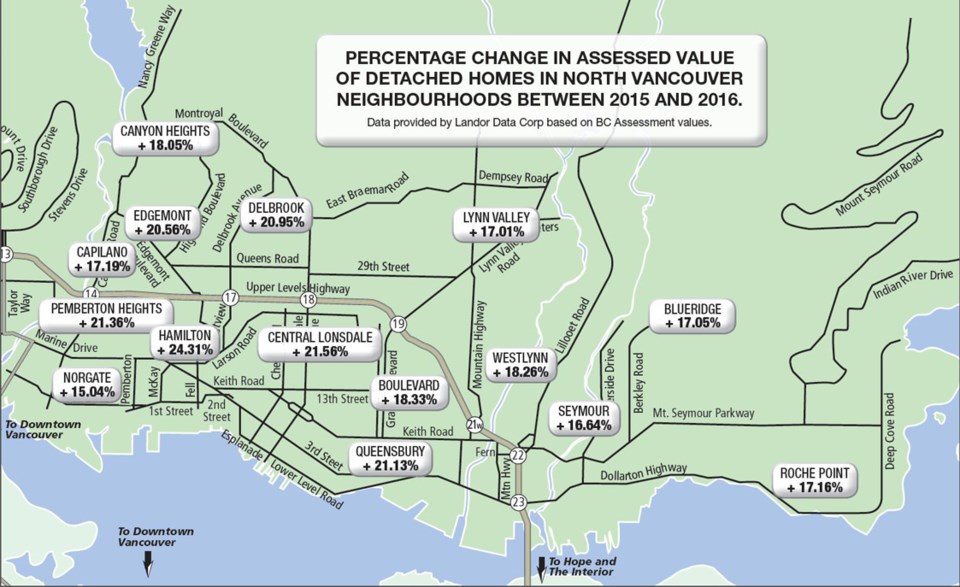

Prices for detached homes in North Vancouver now hover between $1.5 million and $1.7 million according to April statistics from the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, up more than 65 per cent from five years ago. The median selling price of a townhouse is $875,000, while apartments are selling for $467,000.

Those with two or three bedrooms are often more.

“It makes it difficult for people to raise their families in the communities their jobs are in,” said Walton, who adds he’s seen statistics indicating the overall population of the North Shore is falling – even as a buying frenzy fuels a run on multimillion-dollar homes.

During walks in his upper Capilano neighbourhood, Walton said he sees homes that don’t appear to be lived in. “There’s a home I know that I walk by every night that sold for a very high price,” he said. “I haven’t seen any evidence of human activity.”

That’s frustrating for Joanne MacKinnon, 33, who grew up in a home in the Canyon Heights neighbourhood of North Vancouver.

MacKinnon, a registered nurse, worked for Lions Gate Hospital after nursing school, then moved to Kelowna for her husband’s employment. The couple came back to North Vancouver recently when they had a child, planning to live near family.

They’d like to buy, said MacKinnon, but their prospects in the housing market aren’t looking good. “Ideally, everyone dreams of their own home,” she said. “We were OK with a townhouse. But now we can’t afford it.”

MacKinnon said when she checks the real estate listings for anything with three bedrooms for less than $800,000 only a handful of listings come up. “I hear everyone’s overbidding.”

“My husband is a lawyer and I am an RN and we have good paying jobs. You’d think we’d be able to have a family and be able to manage a mortgage,” she said.

Her search has left her “very confused about where everyone is going to live,” she said. “Even renting is hard if we want to stay.”

For Paul Kershaw – a University of British Columbia public policy professor who founded Generation Squeeze to highlight challenges faced by those in their 20s, 30s and 40s – the current housing crisis exemplifies the generational divide between the “haves” and the “have nots.”

“The lottery about when you were born is really driving a lot of this,” he said.

Kershaw was born in the Caulfeild neighbourhood of West Vancouver and spent his early childhood there.

He said he can’t imagine being able to live there now “even though I’m a professor with a good stable job.”

Generation Squeeze researched what young families new to the housing market can buy for less than half a million dollars.

“The reality is on the North Shore only two to three per cent of homes under half a million dollars had three bedrooms,” he said.

That’s already twice the price of an entire single-family home a generation ago (adjusted for inflation and expressed in today’s dollars), he added. “It’s a fundamental deterioration in our standard of living.”

The same trend is playing out across the Lower Mainland, said Kershaw. “Where the vast majority of British Columbians live, housing is becoming out of reach for anyone trying to come into the market for the first time, while simultaneously making incredibly rich those who have had homes for decades.”

In some cases, boomer parents are helping their millennial kids with down payments. But not all boomer parents had homes in the Lower Mainland that allowed them to tap into the real estate rise, said Kershaw. Even among those who do, not all can offer the kind of financial help needed by their kids in today’s housing market.

According to Generation Squeeze research, in 1976 it typically took five or six years to save a 20 per cent down payment on an average home. But now in Metro Vancouver, it takes 23 years. “So you need to be saving for your down payment while you’re still in child care,” said Kershaw.

Mathew Bond, 32, a District of North Vancouver councillor, is another person troubled by the current housing crisis.

“It seems strange to me that owning a single-family home is no longer an option for at least three-quarters of the people in North Van yet two-thirds of our homes are still single family,” he said. “It doesn’t add up to me.”

The situation is partly the result of “decades and decades of decision making that really excluded certain types of housing in our community,” said Bond, who lives in a Lynn Valley basement suite with his wife and 14-month-old daughter.

“We have to look at the way our community is built,” he said. “We have to make sure families have a fair chance at getting a home that suits their needs. It shouldn’t be them outbidding each other in a frantic attempt to get what’s left on the market.”

For those who grew up in detached homes on the North Shore, it’s a mental adjustment. “I think there’s a reckoning between expectations and reality for sure,” he said.

But if millennials are being told to change their expectations, “there needs to be something for us to change our expectations to,” said Bond. “That opportunity isn’t available right now.”

Often there’s a push-back from those in single-family neighbourhoods opposed to greater density.

Greater density can also be a tough sell, said Eby, when it doesn’t seem to help make housing affordable. “It’s almost impossible to sell additional density to communities who believe that the only people who are going to be moving in are investors,” he said.

Many of the same forces that have driven the price of land through the roof have also made rentals increasingly scarce. Many older rental buildings were built under government incentive programs decades ago and are now deteriorating. In the absence of those incentives, few rental buildings have been constructed since. Now older complexes are being torn down to make way for more lucrative market housing projects by developers.

Sarah Bannister knows all about that. The young single mom of two daughters, ages 13 and 10, has lived in Emery Village, a 65-unit rental complex that caters to families, for the past 12 years.

Bannister grew up in an Upper Lonsdale neighbourhood, and works as a hairdresser in North Vancouver.

“Our complex is just like me growing up,” she said. “It’s just like an oasis. (The kids) ride their bikes with all their friends.” There’s a basketball court and a strong sense of connection between neighbours. Her daughters go to school just two blocks away.

But soon all that could be changing. At the end of March, residents got a letter telling them the complex had been sold to Mosaic, a Vancouver development company. “I knew they were going to sell eventually,” said Bannister. “I didn’t think it would be so quick.”

She doesn’t know how long her family will have before they have to move. “But then there’s nothing to rent. There’s nothing affordable,” she said.

Bannister said she currently pays $1,950 for a three-bedroom unit. But that will likely only buy a two-bedroom unit if she has to move.

“All the buildings they’re putting up in Lynn Valley, they’re for sale,” she said. “I can’t afford to buy. There’s no rental.”

She expects the situation will only get worse: “They’re tearing down the complexes around us.”

Bannister said she always thought of the North Shore as a perfect place to raise children. But now? “How can you start a family here?” she said. “No one can afford it.”

Increasingly, young families are being pushed further away from their jobs and community roots on the North Shore. “You can see the tide of money rolling from the west side (of Metro Vancouver) to the east,” said Eby. “The million-dollar line has now moved to Maple Ridge.”

That creates its own set of problems.

Heather Birch, 45, grew up in North Vancouver and has worked in Horseshoe Bay for the past two decades.

She bought her first apartment at 27th and Lonsdale. But when she and her husband decided to start a family a few years ago, buying a two-bedroom unit on the North Shore wasn’t an option.

The couple moved to a condo in Burnaby. “Just by driving over the bridge we saved $100,000,” said Birch.

As her son grew into an active three-year-old, living on the seventh floor of a complex dominated by seniors lost its charm. So recently, the couple sold again. But this time, they couldn’t afford to buy back in, even farther out. Eventually, Birch and her family found a three-bedroom ground-level home in a Coquitlam fourplex.

That decision comes with serious trade-offs, like being further away from her elderly mother, who still lives in North Vancouver. Then there’s the hellish commute.

After dropping her son off at daycare in Coquitlam at 7 a.m. Birch normally drives a stress-filled 45-minute traffic gauntlet to her job.

Coming home is worse – she often spends more than an hour in the daily traffic jam snaking east along Highway 1 and out through Burnaby. “There’s no time of day that’s good,” she said. “You can’t move. You’re trapped.”

Walton sees the growing number of North Shore workers who can’t afford to live here as a very real part of what’s causing the continuing traffic nightmare on the highway.

Birch said she’d love to get back to the North Shore – if only she could afford it. “We’re on waitlists for co-ops,” she said. “They have three to five year waits.”

“I’m a North Van girl,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to raise my son where I was raised.”

Both politicians and academics have suggested solutions to “cool the market.”

Taking a look at the capital gains tax exemption on principal residences is one that Walton and Smith support.

Originally brought in to support home ownership, the tax exemption has allowed serial speculators to make a killing in the hot market, without being taxed on the profit.

“I certainly support both levels of government taking a good look at how to curb principal residence speculation,” said Walton. “For the average citizen in Canada, it’s really squeezing the middle class. I think that’s wrong.”

Smith also favours being able to charge higher property taxes on homes that aren’t the owner’s principal home – something the province currently doesn’t allow.

Australia and Denmark have tackled similar problems by either banning foreign investment in housing or placing limits on the type or amount of housing stock that foreigners can purchase.

That’s something Smith agrees with. “If you are not a permanent resident of a community, there should be some control on how many houses you’re allowed to own,” he said. “This business of people picking up six or eight houses as a place to park money, that’s not the intent of our housing stock. That is happening in West Van.”

In Singapore, high taxes on foreign housing investment are used to help build affordable housing.

A group of Lower Mainland academics also recently suggested a property tax surcharge tied to income tax (with the exception of retirees) designed to target people who own high-end property yet don’t work and pay income tax in B.C.

“There’s an overwhelming support for it,” said Eby.

Except, notably, from the provincial government, which raked in $1.15 billion in property transfer tax to provincial coffers in the last fiscal year ($98 million of that from property sales on the North Shore). The economic boom in real estate has cushioned slides in other sectors.

Eby finds that confounding. “It’s a huge discussion and there’s an overwhelming consensus that the government needs to do something. The devil’s always in the details about what that something is.”

In the meantime, even some of the “winners” in the housing sweepstakes have been left wondering what they’ve won.

“It’s one thing to sell but if you can’t find anything to buy in the community, they’re having to leave,” said Smith.

Count Heather Hirst of Moodyville as one of them.

Hirst lives in the 500-block of East First Street in North Vancouver, an area of modest 1950s bungalows just up from the waterfront port terminals.

She bought her house 12 years ago for around half a million dollars.

“A lot of the neighbours knew each other. A lot of them had been there for years,” she said.

When the port approved plans allowing a bank of large new grain terminals to be built immediately in front of their homes in 2013, “we were devastated,” said Hirst.

So when a developer offered to buy out the property owners in a land assembly, many of them took the offer, including Hirst.

“I got a lot of money for my house,” she acknowledged – $1.35 million.

Since January, she has continued to rent her old house back from the developer.

“I was thinking I could just move up the block,” she said. “I figured I could get a house similar to mine. Mine wasn’t in great shape. I wasn’t looking to get a mansion.”

Turns out she was wrong.

Hirst started looking at houses in the range of $1 million to $1.5 million in January. She put offers on four rundown homes in North Vancouver, which all attracted multiple offers and sold for between $100,000 and $300,000 above the list price.

In some cases, “I offered over $200,000 above list and didn’t get them,” she said. She didn’t want to downsize to a townhouse or condo and instead started looking in Port Coquitlam. “I found out they were doing the same,” she said. “I started getting worried I’d be out of that market too. I panicked.”

She bought a house in Port Coquitlam recently for $950,000 over the Internet without ever seeing it in person. “It was above list with no subjects,” she said.

“I don’t think I’ll ever get back to North Van,” she said. “I don’t think I’ll ever have that opportunity.”

Next week: There goes the neighbourhood. North Shore residents grapple with rapid changes to their neighbourhoods being driven by an influx of new money and sharply rising land values.