Explosives management contractors will spend the next two weeks hunting for possible munitions left and forgotten on the former Blair Rifle Range site in North Vancouver.

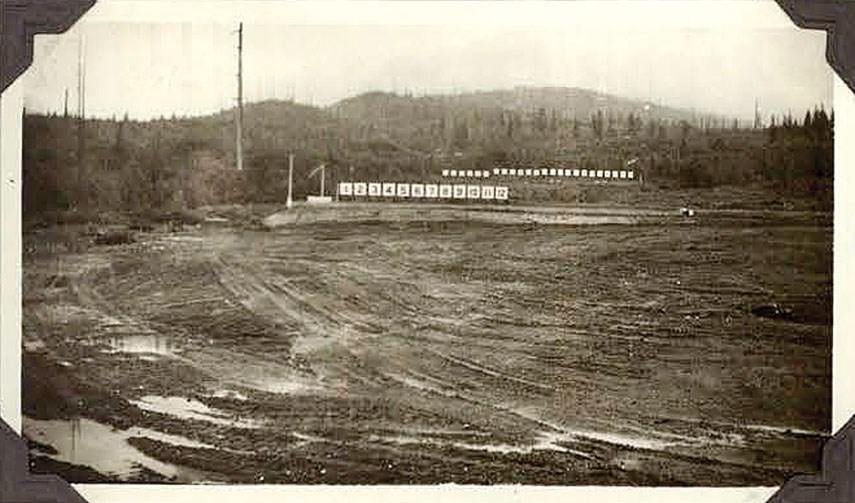

The lower hundred acres of the site fronting Mount Seymour Parkway was a military rifle range from the 1931 until 1968, until ownership of the land was transferred to the province and Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.

Since that time, it became a destination for hikers and mountain bikers. In 2016, CMHC put up No Trespassing signs around the land over liability concerns. The province reached a deal with CMHC earlier this year to formally allow trail users on the site, with the North Shore Mountain Bike Association taking on responsibility for trail maintenance.

But the Department of National Defence is deploying technicians from its Unexploded Explosive Ordnance program this week to double check that there wasn’t anything dangerous left behind.

“While we don’t have any evidence to suggest that the range was used for anything other than rifles or handgun training, out of an abundance of caution and concern for the local community, we will be conducting a site survey from Feb. 18 to March 3, 2018,” the statement from the department read. “Walking and biking trails will remain open while the investigation is underway, so you may see technicians walking through the woods, or digging into the ground. In the unlikely event we find something serious during the site investigation, we will provide an update to local residents.”

Whether there ever was anything more than pistols and rifles on the site though is an open question, according to Donna Sacuta, a local historian who published a history of the Blair Rifle Range lands in 2015.

“It’s unclear. In some of the reports that I looked at, it was suggested that they did grenade practice there. I interviewed some people at the Westminster Regiment … and through into the ’60s, they said they were doing mortar practice there as well,” she said.

But, Sacuta added, memory can be fallible. National Defence is aware of those anecdotes, according to an emailed response from the defence department, but studies done in 1977 and 1995 using visual inspections, excavations and scanning with metal detectors found no evidence of it.

Not up for debate though is whether there are other nasty things left in the soil, according to two environmental reports commissioned by CMHC in the 1990s.

“In both of those reports, they reported high levels of lead, zinc, heavy metals,” Sacuta said. “Which is not unreasonable. When you’re firing bullets and so on, you’re going to have a lot of contamination in the soil, especially after decades of use. There was some leaching going into the waterways at the site.”

Both of those reports acknowledged there were anecdotes about dump sites for unexploded munitions but the studies weren’t resourced enough to fully investigate, Sacuta said.

While the National Defence survey may shed light on potential explosives left behind, Sacuta said the technicians will have their work cut out for them. Since the range was decommissioned in 1968, much of the land has been reclaimed by trees.