North Shore residents are among those spending the most time stuck in traffic in Metro Vancouver and are feeling the most frustrated about its impact on their lives, according to a study by the Mobility Pricing Independent Commission.

Solving that problem is, not surprisingly, also highest on their list of transportation priorities.

But whether some kind of new “mobility pricing” – which could involve tolls on roads, bridges or distance travelled at particular times of day – should be a part of that will likely be the subject of intense discussion.

This week, the independent commission kicked off what’s expected to be several months of public consultation on the issue.

“Almost everyone in Metro is frustrated about traffic,” said Allan Seckel, chairman of the commission. “It’s costing them time and money every day.”

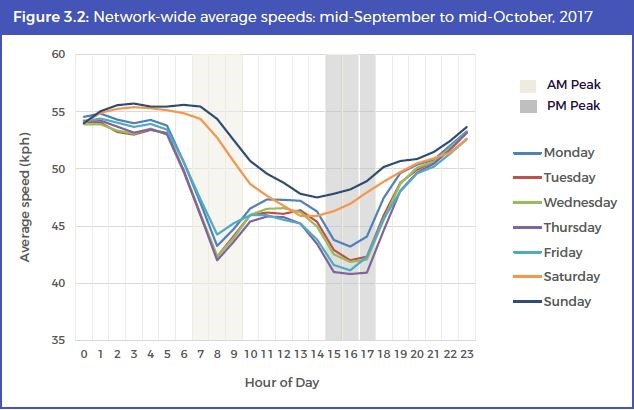

About 30 per cent of the time people spend driving in rush hour is spent sitting in traffic snarls, according to the commission’s preliminary research.

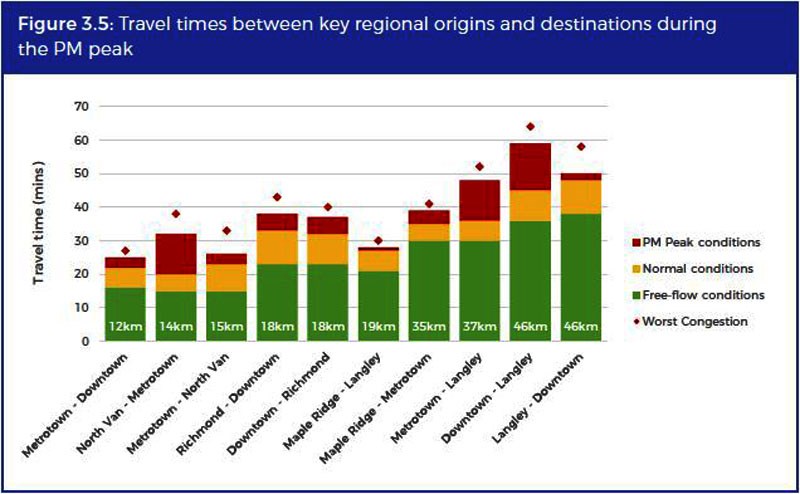

North Shore drivers are among the worst affected, along with residents of Langley, the study found.

Graphs contained in the commission’s report show North Shore residents experience some of the biggest delays between “normal” driving conditions and driving during peak rush hours. (Langley is one of the few areas where even worse patterns were noted.)

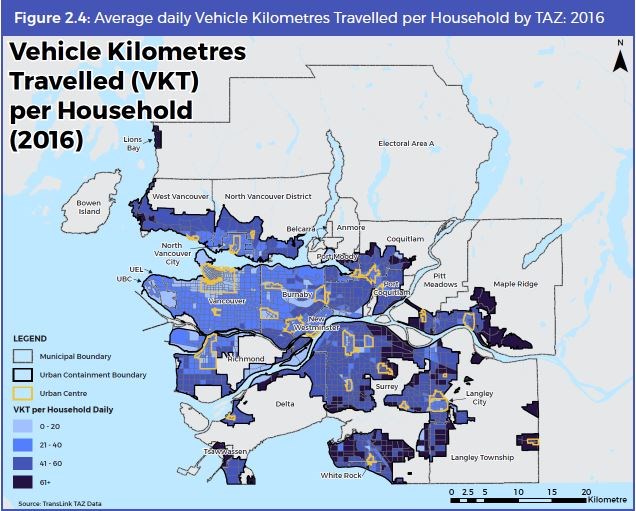

Information gathered from an online poll conducted among 1,000 Metro residents by the polling company Ipsos in September showed 76 per cent of trips were done as either a driver or a passenger in a car by North Shore residents. Only 11 per cent of trips were taken on transit while 10 per cent were made on foot and one per cent were made on bicycles. The report showed the number of kilometres driven each day per household increased in less densely populated areas, including the western parts of West Vancouver and the upper reaches of most areas of the North Shore, where households drive over 60 kilometres daily. People with higher incomes are likely to drive more.

The idea behind mobility pricing – or “de-congestion pricing” as the commission refers to it – is to take some of the peak load of vehicles off the roads by giving people financial incentives to take transit and/or to travel at different times of day by imposing some kind of tolls or fees connected to where or when people drive or the distance travelled.

But not everyone is a fan of using mobility pricing as a solution.

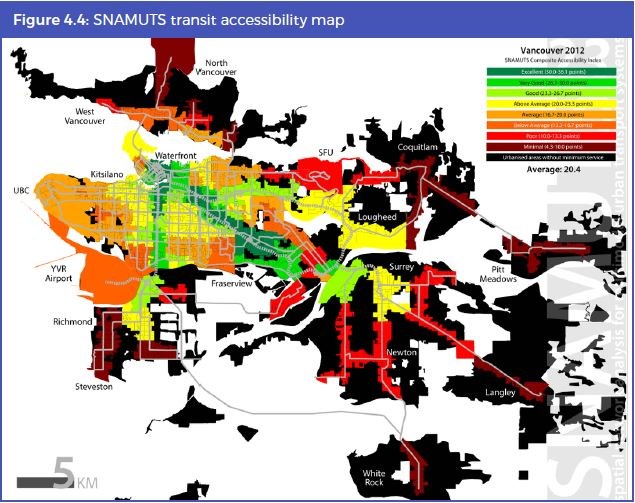

“How does congestion pricing work if you have no alternatives?” asked District of North Vancouver Councillor Roger Bassam. “If there’s not another way (to get around), all I’m doing is paying tax. I still have to get to where I’m going.”

Bassam said a mobility pricing system will unfairly target people making less money, because they are least likely to have a choice about when they travel, whereas wealthier people won’t mind paying more for less congestion.

Bassam added when concrete information about possible tolls or fees is presented by the commission next spring, it’s likely to be politically unpopular.

“I think people don’t understand mobility pricing. They don’t have a clue what it means,” he said. But Bassam said if people are asked if they want to see tolls on bridges, “they say no.”

“That’s why the NDP is in government right now,” he said.

The commission plans to hold public engagement sessions, and stakeholder workshops over the next several months, including sessions on the North Shore. The public is also being invited to weigh in online at ItsTimeMV.ca.

A final public report is expected in the spring.