The number of people commuting to the North Shore has risen nine per cent since the last census, a statistic that likely goes a long way to explaining our daily traffic jams.

Statistics Canada released a batch of data on commuting habits last week, showing 1,880 more people who regularly work on the North Shore in 2016 but live elsewhere in the Lower Mainland, compared to 2011.

And despite a local population growth of 3.3 per cent in that time, the number of commuters heading south over Burrard Inlet each day has actually gone down by about 0.5 per cent, the data shows.

In total, 41.4 per cent of the North Shore’s workforce comes from elsewhere in the region, according to the census, up from 39.6 per cent in 2011.

“Interestingly enough, people are commuting into your system as opposed to commuting out,” said Andy Yan, director of Simon Fraser University’s City Program.

The stats, however, only include people with a “usual place of work” meaning they do not capture those who work on short-term contracts like construction trades workers who may only be at one project for a matter of days or weeks. In 2014, the study by the province found a direct link between demolition and building permits in the three municipalities and traffic flow over the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing.

District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton said, taken together, that amounts to the smoking gun in the mystery over the North Shore’s traffic congestion.

“There’s no question that it is,” he said. “It just verifies what we’ve observed the last five or six years with the massive increase in the number of people in the trades who are commuting across the Ironworkers ever day to the North Shore. … And then all those folks are getting right back into the same traffic, trying to get over the Ironworkers in the afternoon between 3:30 and 6 p.m.”

Labour stats from the census show the number of North Vancouver residents who work in the trades has fallen by four per cent in the last 10 years. And, Walton added, the cost of housing here is a significant factor.

“We have increasing numbers of people who are commuting because they can’t afford to buy entry-level housing here,” he said.

No secret to anyone, our commutes are getting longer. The average duration for DNV residents was 26.6 minutes (from 25.1 minutes in 2011). A typical city resident spends 26.2 minutes between home and work, up from 24.3 minutes. West Vancouverites have the shortest commute at 26 minutes up from 24.6.

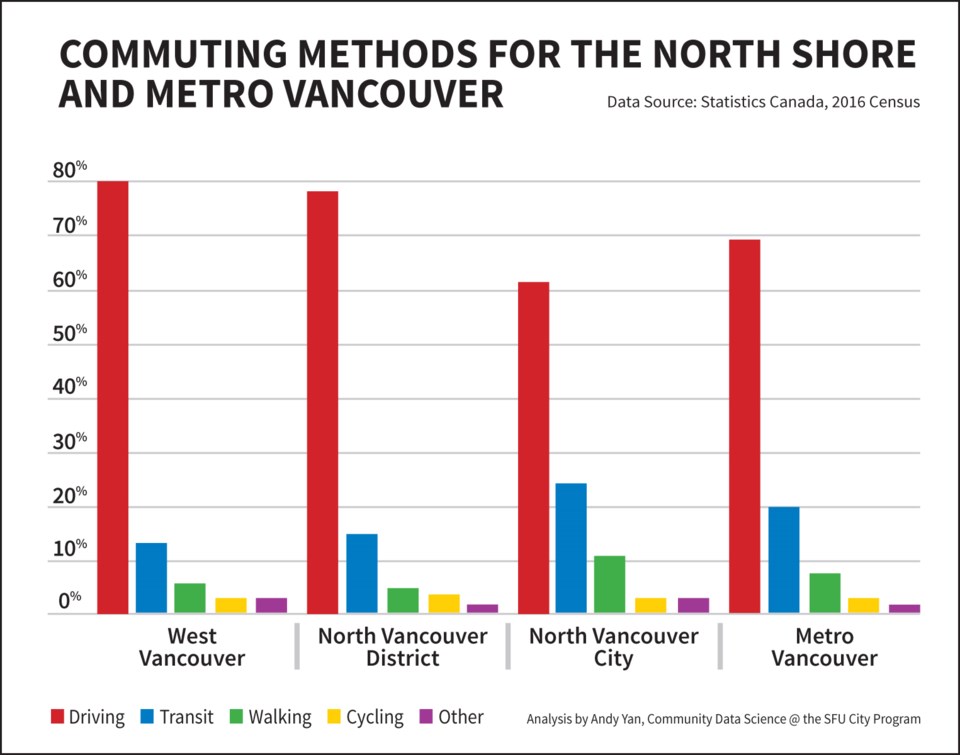

There have been some shifts in how we get around. In the City of North Vancouver, 57.6 per cent of the city’s commuters drive daily, down from 58 per cent. Only one out of 15.8 carpool with someone else according to the data. Just under one-quarter of commuters in the city take transit, up from 22.8 per cent five years ago. Eleven per cent walk and 2.5 per cent of commuters are daily cyclists, up from two per cent.

In the District of North Vancouver, 73.2 per cent of commuters are behind the wheel. Only seven per cent of them bring a passenger. Three per cent choose to bike, up from 2.1 per cent in 2011. Walkers make up only four per cent. Public transit decreased from 14.9 per cent in 2011 to 13.6 per cent, still well below the regional average of 20 per cent.

West Vancouver’s commuters were the most likely to drive at 74.8 per cent with less than six per cent carpooling. Cyclists account for 1.7 per cent of commuters, a number that’s gone unchanged since the last census. West Vancouver also experienced a drop in transit usage from 13.6 per cent in 2011 to 11.6 per cent in 2016. Walkers make up roughly five per cent of commuters from West Vancouver.

Walton said the numbers indicate the district is on the right track with its official community plan, which foresees 85 to 95 per cent of residential growth happening in transit-oriented town centres where residents will have the option to carry out most tasks without a car.

“That is the strategy that was articulated 10 years ago and I don’t think that’s going to change. Certainly we need to be building those town centres and working in an accelerated way to in taking advantage of affordable housing opportunities,” he said.

Council is frequently chastised for its approval of condo developments because of their supposed impact on traffic. But Walton said, slowing or stopping development will only make matters worse.

“To grind everything to a halt and have no additional supply into the North Shore, in a region that is growing very, very quickly, you’re going to exacerbate the situation where you’ve probably got more and more people who are critical to jobs on the North Shore having to commute because they can’t find housing here,” he said.

For some of the folks arriving here each morning, transit won’t be an option, particularly if they’re coming long distances or coming with tools and supplies as trades workers do, Walton noted.

What might be key to unlocking the gridlock is mobility pricing, which the province is currently studying, Walton added.

“It will result in people changing their behaviour marginally. Not most people, but all you need is five or 10 per cent of people to change their behaviour and you can free up capacity during peak hours,” Walton said.

Yan said if we want to alleviate traffic, we need to do a better job of shifting our mode share away from single-occupancy vehicles, not necessarily build the fabled “third crossing.”

“The vast majority of people living on the North Shore are car dependent,” he said. “It may be more about the issue of a much better transit network on the North Shore.”

Because of the sprawling nature of the North Vancouver and West Vancouver districts, they have a tougher task ahead of them in building the types of neighbourhoods that get good transit connections.

“A robust transit network needs, I think, a certain level of density to help drive it,” he said.

And, Yan noted, if we’re wishing the daily traffic jams would just go away, we should be careful what we wish for. Traffic means jobs and economic activity that generates the tax revenue we rely on to pay for services.

“It’s not necessarily a bad thing that you’re developing into your own job centre,” he said. “‘No, no. I don’t want more jobs in my community.’ I have to admit, in my career, I’ve never heard that before. It’s a really interesting kind of dilemma for the North Shore.”