You cannot drag the whole of the past with you.

So says archivist Janet Turner.

Standing in the main room at the North Vancouver archives, with its large windows letting in the morning light, she explains that part of her training is to determine the long-term value of items that end up in the converted school-house space.

Material with ephemeral interest doesn’t persist, she notes. Diaries, for example, may have an eye to posterity, but not all diaries earn a spot in the archives’ holdings. Context, date, condition, and the identity of the author may determine if a diary stays or goes. Another aspect of archival value is rarity, such as photos from the 1800s.

Also under consideration: Was the item valuable to its creator? Would it hold value to the community at large?

It’s difficult to anticipate what may or may not be of archival interest to the public decades from now, and that’s why Turner and her colleague, reference historian Daien Ide, don’t try to guess.

“You never know what someone will be interested in 10 years from now, 100 years from now,” says Ide.

The decision-making process involves set rules and criteria that both Turner and Ide have trained many years for in order to preserve pieces of history.

“Archives become the longtime memories that outlive our fragile memories,” explains Turner.

One diary that did make the cut displays an interesting historical mark. It’s a B.C. Mountaineering Club journal from many years ago that was kept in a cabin on Grouse Mountain. One entry recounts how a bear broke into the cabin and made quite a mess.

The best part of the journal is not the entry itself, however, but a large claw mark on the outside of the book left by the furry rascal that knocked it off the table, perhaps in a final flourish of bad behaviour as it ambled back outside. It is one of Ide’s favourite archived items, and just one of many that hold the history of North Vancouver’s past.

The North Vancouver Museum and Archives organization has been in its current location beside Lynn Valley elementary since 2006. The archives occupies the second floor of the space collectively called the Community History Centre, which also houses offices on the first floor.

The location has experienced many incarnations over the years. It started with a one-room school house that grew into a bigger wooden school by 1912, then added a third and fourth structure over the years. Not all the original structures are still standing, but remnants remain (one now houses a nearby parent participation preschool). Eventually, the main building was redeveloped specifically to house the archives and related offices.

Recently, the archives hosted an open house for community members to explore the space and learn more about what it offers.

A few days before the event, an early morning visit finds a building that still resembles an old school in its exterior structure but the interior has clearly been redesigned for a new purpose.

Instead of lockers jammed with papers and old PB&J sandwiches, the building is bright and airy with high ceilings and fresh paint. Archival photos and posters line the walls and a large desk welcomes visitors at the entrance.

Take an elevator to the second floor and look to your left as you step off. The hallway is used as an exhibit space that displays aspects of the archives’ holdings. On this day, there are enlarged copies of black-and-white photos from the 1940s.

Straight ahead is the large reading room, so called because it’s meant for visitors to peruse archival material in place. Because it is irreplaceable, archival material cannot be borrowed like library items, explains Turner. This large room is set up for visitors to access archival material without taking it out of the building.

The centrepiece is a long, wooden table stretching down the middle of the room. Known as the Burrard Dry Dock Table, it was built by shipyard workers around 1925 and was used in a boardroom there. The table was salvaged from the closed shipyard in 1992 and has been with the archives ever since, restored by a local cabinet maker.

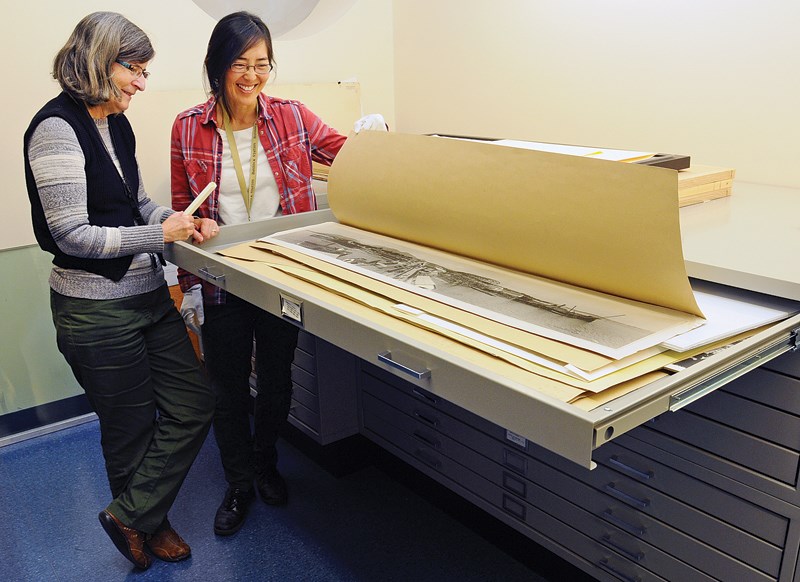

There are three surfaces, including the dry dock table, big enough for visitors to roll out maps (some of which are very large). Maps are a very popular item for visitors, notes Turner.

Maps most looked at include old flume routes, locations of former zinc mines and water pipes, lost streams and trails, and locations of long-gone mountain cabins.

The archives has more than 300 maps in its holdings. However, one “holding” can include multiple pieces. For example, records acquired from a local forester who lived on the North Shore include hundreds of annotated maps that are counted as one aggregate holding. Photos are also popular, and visitors can order digital copies of ones they want to keep.

The large outdoor mural that is part of the public art display at The Shipyards site in Lower Lonsdale is from a photo the archives provided. Metal recreations of employee cards also used in the display are designed from archival personnel records.

“I think they appeal to us underneath a logical level,” says Turner of the popularity of archival photos. Photos don’t need to be analyzed like a building plan or property map, they can just be enjoyed, she adds. In some ways, looking at a photo allows a person to be part of that one moment captured in time.

“To me (the photo) was there on a given day and participated with that person,” says Turner.

Other records at the archives include ship plans, technical drawings and directories. Stacked neatly in low bookcases lining one whole wall of the reading room are multiple directories (originals) containing details of past North Shore residents: names, addresses and jobs, as well as names of spouses and children, and whether a person owned or rented their property.

The directories show who has lived in a house over generations, so visitors can trace a person or an address over many years. The directories start in 1901, showing information for the entire province, then narrow down over the years to the Lower Mainland and eventually North and West Vancouver.

The largest single holding on site are files from Versatile Pacific Shipyards, rescued when the shipyard folded. The collection includes building plans, administration records, contracts, personnel records, staff newsletters, and 5,000 photos.

“It was the principal industry on the North Shore for many decades,” says Turner of the significance of the Versatile holding, noting the company was an economic linchpin of the area for a long time. “Its closure represented a turning point in Lower Lonsdale’s development.”

There are still some restrictions on some of the material, meaning not all of it is up for public consumption just yet, such as some personnel records, mainly for privacy concerns. That applies to other items on file as well. However, restrictions on material have to be “reasonable,” such as only limited until the person named in the record has passed away. If there are too many restrictions placed on an item, the archives won’t take it since the material is meant to be shared.

Computers and other references in the room, such as microfilm readers, allow access to self-serve databases for visitors to search archive holdings. Turner and Ide are also on hand to help visitors navigate the system to find a specific item or a starting point into a subject area.

Part of the open house event, and the private tour on this day, is a visit to the secure storage area, which is usually closed to the public. Material from this area is retrieved by request.

Stepping inside the large room, it is immediately noticeable that the temperature is a bit chillier. Climate is moderated in this room to preserve the archival material, and measures are taken to control the temperature, humidity, light level, ventilation, and even pests (silverfish sometimes make an appearance).

Around 15 tall, metal shelves stretch along the length of the room, closely packed together. A handle on the outside of each section is spun to slide the shelves apart revealing more shelves within the shelves, each packed with archival material.

The room contains various media, including photos, negatives and paper records, as well as audio recordings and video on tape and old-school movie reels.

“Records can occur in any sort of medium,” says Turner as she tours the area, pointing out items of note.

Among the more interesting pieces are a collection of handwritten diaries by North Vancouver resident Walter Draycott. The entries are written in pencil because Draycott wrote many of the diaries when he was a military topographer in the First World War.

As a soldier serving at the front, he was often knee-deep in water and so he wrote in pencil as pen would run when it got wet. The books are pocket-sized so they could fit in the front pocket of his uniform. When he returned to his home in Lynn Valley, Draycott continued to write and his journals and correspondence provide prolific detailed notes of the community throughout his lifetime. Turner has read all but one of the numerous pieces, which number 73 in total.

There is too much archived material to outline in one short story, but another interesting item Turner highlights is an adoption contract that is one of her favourite items for both its content and esthetic.

The contract is from 1910, but the writing, wax seals and ribbons that adorn the paper make it appear medieval. The notice lays out specific terms of adoption for a little girl named Elley from England to a relative on the North Shore.

At its core, archival material is a record of a community and its people; personal, professional and civic happenings. It can tell a story, paint a picture, and provide details. But some details are lost, and some mysteries still remain.

When asked about her favourite item, Ide pulls out an old photo album that started its archival journey at the West Vancouver archives, which didn’t have any information about the album’s owner.

However, many of the photos appeared to be taken in North Vancouver so the album was passed on to Ide, who spent many months investigating and researching until she discovered that the album belonged to “Miss J. Conroy.”

While she was able to trace much about the Conroy family, including some living relatives, Ide also discovered that “J. Conroy” was Jennie Conroy, who was murdered in 1944 at the age of 24.

The case was never solved.